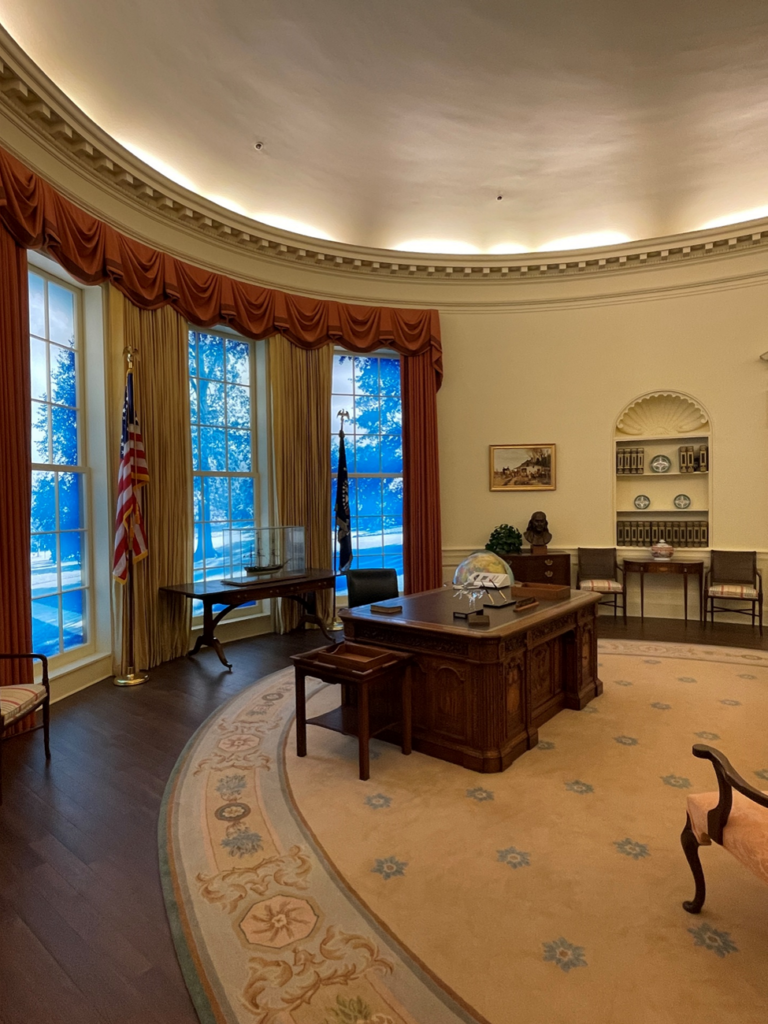

James Earl Carter Jr.’s Presidential Library is striking in it its simplicity. Japanese maples and star magnolias guard the entrance, quietly tucked away at the end of a curving pathway. Much like its namesake, the Carter Presidential Center balances modernity and tradition: It sits just five minutes from metropolitan Atlanta, one of America’s most dynamic cities, but its style reflects a reservedness and soft-spokenness exclusive to President Carter’s beloved South. Indeed, President Carter was a modernizer in the White House who never strayed far from his roots.

Navy Years

The first in his family to attend college, President Carter credits the Naval Academy for developing his technical mindset. In the early 1950s, the U.S. Navy underwent a technological revolution. Captain Hyman Rickover, who would later be promoted to Admiral, led development efforts for nuclear powerplants.1 Carter became Rickover’s protege. Though Carter’s participation in the Navy’s burgeoning nuclear program would be cut short by his father’s death in 1953, Rickover profoundly influenced Carter. In a 60 Minutes interview, Carter noted that “he demanded more from me than I thought I could deliver.”2 Though Rickover was often reviled for his abrasive personality, he put Carter’s abilities to the test in a way that would only be matched by the presidency.

Georgia Politics

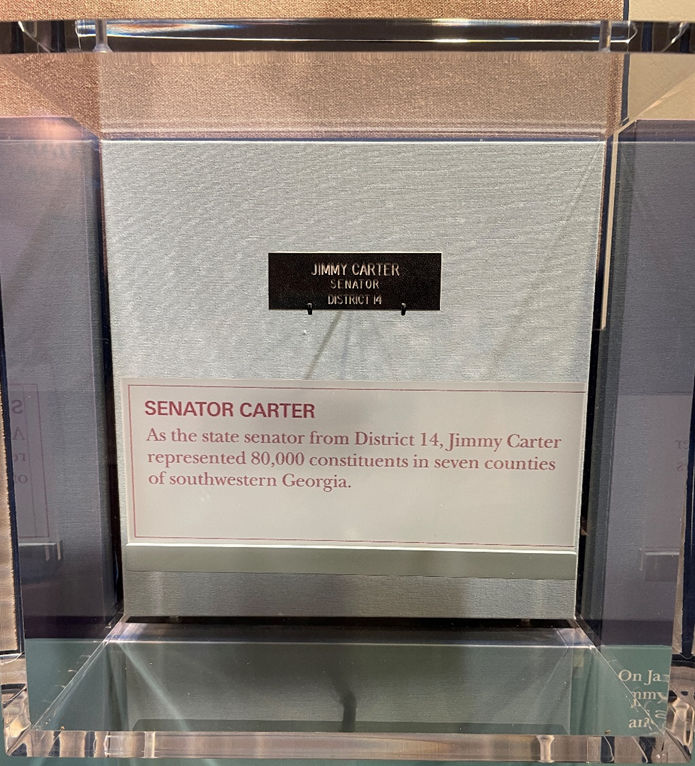

As a thirty-eight-year-old in 1962, Carter ran for the Georgia State Senate. He prevailed after a court mandated a new election, due to significant irregularities during the first round of voting.3 His victory in 1962, a political outsider versus an opponent tainted by corruption, foreshadowed the result of his 1976 contest against Gerald Ford.

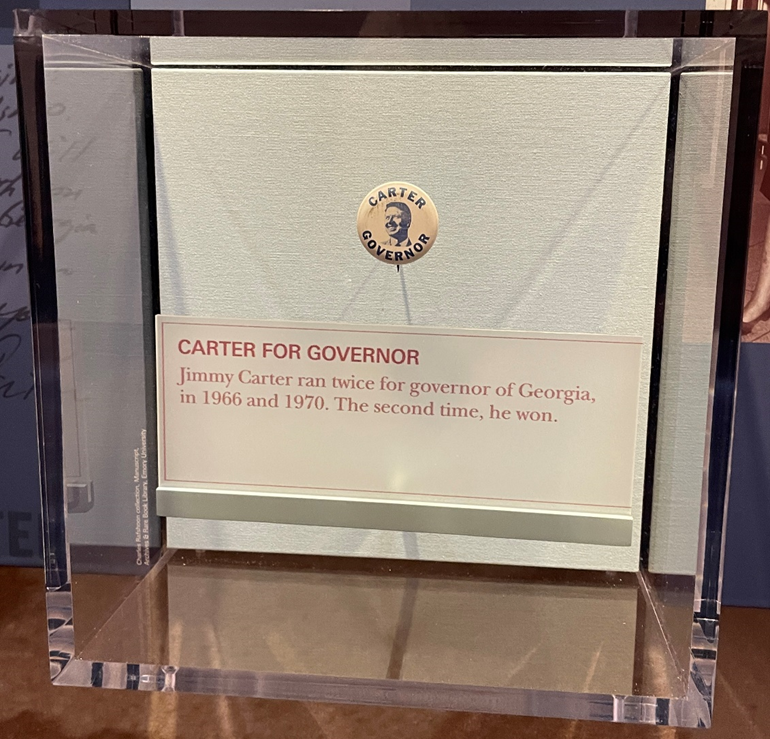

In 1966, Carter sought the Governor’s Mansion in Atlanta. He fared poorly in the Democratic primary (effectively the only race that mattered in single-party Southern states) and lost to the pro-segregation populist Lester Maddox.4 Carter held progressive views on Civil Rights, which he inherited from his mother; whenever his church voted on integrated worship, he and his wife Rosalynn were the only supporters.4 He took a much different approach to his successful 1970 gubernatorial run. He opposed busing, a program to desegregate public schools, and even won the endorsement of Lester Maddox.4 His racist appeals caused uproar: The Atlanta Constitution newspaper derided him as “ignorant, racist, backward, [and] ultraconservative.”4 Nonetheless, he prevailed.

As Governor, Carter returned to his liberal civil rights platform, expanding employment opportunities for African Americans in state government, alienating his supporters.4 Though he achieved measurable success reforming the state’s bureaucracy, he had a troubled relationship with fellow Democratic politicians.4 The same problems that plagued Carter’s political career in Georgia—alienated voters and poor relations with would-be political allies—ultimately derailed his 1980 presidential re-election bid.

The Road to the White House

Being from the South was a political liability for ambitious Democrats. Reactionary racial politics worked in the South, but they did not resonate with Democrats elsewhere. The Democrats’ poor showing in 1972 against incumbent Richard Nixon, however, provided an opening for Carter in 1976. McGovern, a left-wing Senator, pledged to end the Vietnam War immediately.5 Nixon effectively retorted by promising to end the draft, guiding America to what he would eventually call the “peace with honor” solution.5 Carter knew that a more practical approach to campaigning was necessary.

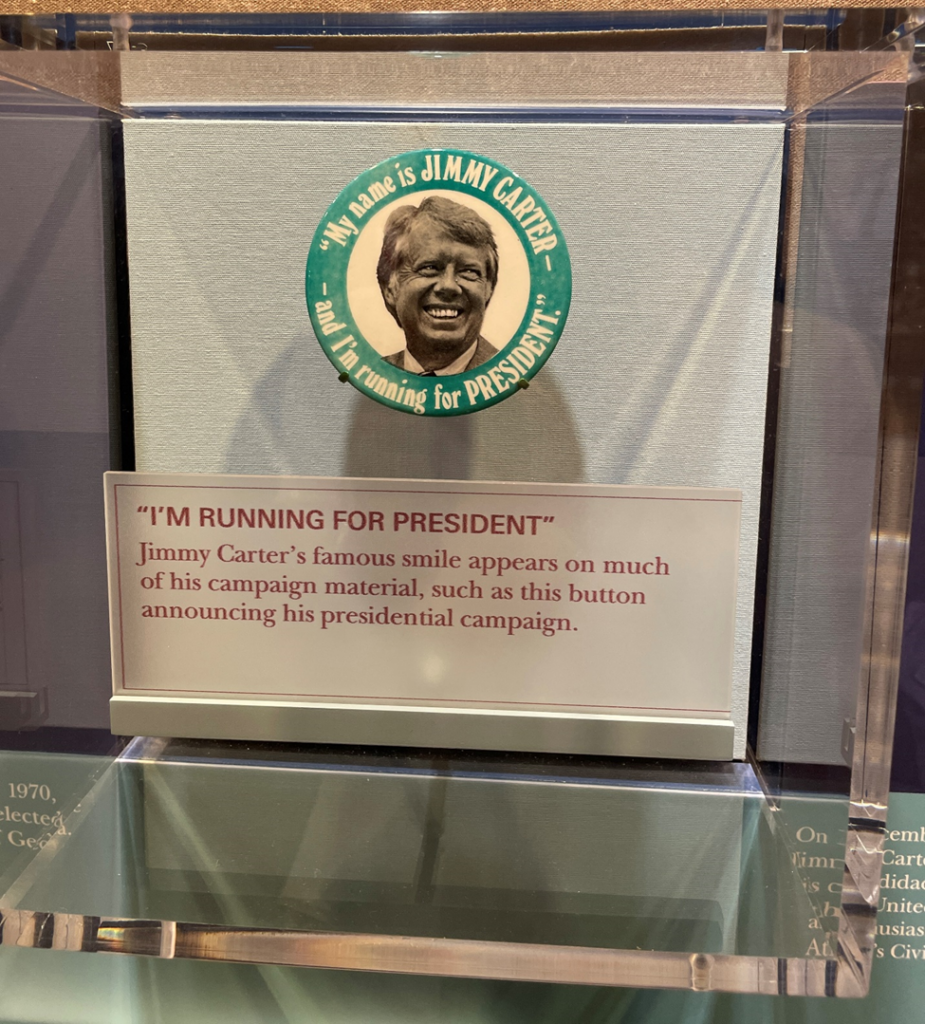

The 1976 Democratic primary was a crowded field. Reforms originating from the contentious 1968 Democratic National Convention weakened the influence of party bosses over the selection of nominees. Seventeen hopefuls sought the Democratic ticket.6 Carter’s strategy, novel at the time, established the model for today’s primaries. Unlike his opponents, who ignored early states with low delegate counts, such as Iowa and New Hampshire, Carter sought to build momentum and overcome voters’ skepticism about his lack of a national profile.6 Carter’s popularity grew, and his formidable opponents slowly filtered out. He faced a difficult test against California Governor Edmund Brown.6 Brown won major victories in California and New Jersey, but Carter won the nomination after Senator Henry Jackson of Washington offered him his delegates.6

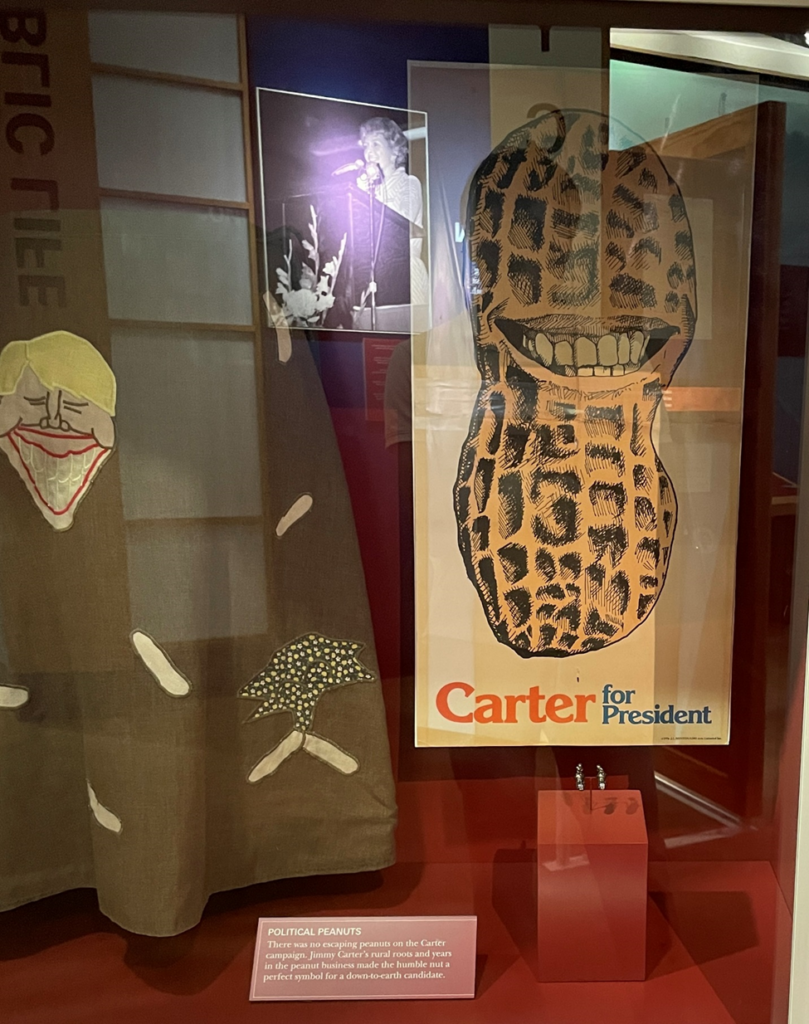

Aggressive engagement with the public helped him carry early states. Though his campaign had limited means, he established an impressive ground operation: Carter’s Peanuts, loyal supporters from his hometown of Plains, canvassed door-to-door, staying in homes to reduce costs. A postcard campaign helped supporters persuade friends and family; he ran the 1970s equivalent of Barack Obama’s internet-savvy 2008 campaign.

Carter’s shock victory in the Democratic primaries meant that he had no trouble defeating incumbent Gerald Ford and the Republican Party, hobbled by Watergate, in 1976.

White House Years

Domestic Policy

America’s economy showed warning signs in the late 1960s. Fiscal stimulus, like President Johnson’s Great Society welfare programs, the deepening U.S. military presence in Vietnam, and tax cuts passed in 1964 caused the economy to overheat.7 By 1969, inflation reached 5.75%.7 Modest Federal Reserve rate hikes proved ineffective.7 President Nixon imposed 90-day wage and price controls in August 1971, but the effectiveness of these measures was short-lived. The October 1973 Arab oil embargo, imposed in response to U.S. support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War, compounded Americans’ economic pessimism.8 The embargo, which was lifted in March 1974, became ingrained in the public conscience as an example of the dangers of dependence on foreign oil producers.8 President Nixon signed the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act in November 1973, creating a bizarre pricing system and extending price controls.8

President Carter sought to promote energy self-sufficiency from the beginning of his term. In an address to a joint session of Congress in April 1977, he outlined ambitious targets for 1985, including reducing energy imports to one-eighth of American energy consumption, lowering year-over-year energy demand growth to sub-2%, and powering 2.5 million homes from solar energy.9 He pushed for taxes to encourage industries to substitute natural gas or oil with coal, taxes on vehicles that failed to meet federal fuel economy targets, tax credits for solar equipment installed by homeowners, and the creation of a new Department of Energy to replace the American Gas Association and American Petroleum Institute.10 Carter wasn’t successful at achieving all aspects of his reform package: Congress shrunk the list of industries subject to taxes for using oil and natural gas for industrial heating and rejected his plan for a gasoline tax that increased by five cents per gallon every year until a national consumption target was met.10 President Carter pursued market reforms for the natural gas industry, culminating in the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978. A gradual transition to market pricing, overseen by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, expanded America’s natural gas supply.11

President Carter led the U.S. during the 1979 Iranian Revolution, a more dramatic energy price shock than the embargo six years before. In 1980, the U.S. spent 4.5% of GDP on oil imports, compared to 2% in 1974.8 Carter’s policies did not provide immediate relief to consumers, contributing to his 1980 election loss. His efforts bore fruit in the 1980s, however. Between 1980 and 1985, American oil imports fell from 8.2 to 4.5 million barrels per day.12 Domestic oil and gas production flourished.

Foreign Policy

President Carter’s foreign policy successfully brought multiple Nixon Administration initiatives to fruition.

Middle East

President Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger practiced “shuttle diplomacy” to contain the fallout of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.13 American military aid helped the Israelis turn the tide of the surprise attack led by Syria and Egypt; however, Nixon and Kissinger pressed the Israelis to strive for peace with their powerful adversaries.13 The Israelis partially withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula, which they annexed from the Egyptians during the Six Day War of 1967.13 The Nixon Administration left Carter with a stable foundation to pursue Egypt-Israeli normalization, but several contentions remained.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, and President Carter convened at Camp David in 1978. The negotiations got off to a poor start: American officials even had to separate the Egyptian and Israeli delegations, serving as a conduit for talks.14 The status of the fourteen Jewish settlements in Sinai and other territories that Israel claimed during the Six Day War threatened to derail peacemaking efforts.14 Palestinian rights naturally emerged during negotiations, but, as Osama El-Baz, Egypt’s chief negotiator, stated in 2003, the Egyptians lacked the “power of attorney by the Palestinian people” and thus agreed to limit the scope of the agreement.14

The negotiators reached an agreement after thirteen days on September 17th, 1978, establishing full diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel.14 Though the agreement didn’t deliver a comprehensive peace plan for the Middle East–in 2003, President Carter acknowledged that the Camp David Accords allowed settlement in the West Bank to go unchecked, creating a powder keg situation–it sparked hope for future talks.14

Asia

President Nixon’s iconic 1972 visit to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) set the backdrop for President Carter’s formal establishment of diplomatic relations with the PRC.15 Nixon’s visit resulted in the Shanghai Communique, which affirmed mainland China’s and America’s commitment to resolving their disagreements.15 Both mainland China and Taiwan wanted the U.S. to recognize only one China, while Nixon wanted both parties to have diplomatic recognition (ultimately, the U.S. supported the PRC’s 1971 ascension to the United Nations, replacing Taiwan, where it wielded veto power as a permanent member of the Security Council).15

President Carter continued Nixon’s progress, which was halted by the Watergate scandal and conservative opposition. Liaison offices in Beijing and Washington, D.C., opened in 1973, allowed American and PRC negotiators to iron out differences.16 The U.S. agreed to solely recognize the PRC and terminate its mutual defense pact with Taiwan, though it would continue to “maintain cultural, commercial, and other unofficial relations with the people of Taiwan,” as enumerated in the Shanghai Communique.16 On December 15th, 1978, President Carter notified the American public that the U.S. would switch diplomatic recognition of China from Taiwan to the mainland on January 1st, 1979.16

A diplomatic feat spanning three presidencies, formalizing ties with Communist China offers lessons for American policymakers today. Lawmakers once supportive of China’s economic rise now warn the public of the threat Beijing poses to American interests. Presidents Biden and Jinping struggle to address shared concerns, such as maritime security. A sustained commitment to dialogue bridged an insurmountable gap in the 1970s. Contemporary Chinese and American leadership would be wise to manage tensions, rather than encourage confrontation.

Poor Salesmanship

The causes of President Carter’s 1980 downfall are widely known. The taking of American embassy staff in Tehran as hostages, Soviet aggression in Afghanistan, and challenging economic conditions weighed heavily on voters’ minds. Nonetheless, President Carter presided over a robust domestic and foreign policy agenda. He struggled to persuade the American people of his competence, however. His July 15th, 1979 “Crisis of Confidence” speech best represents his political struggles. He recognized his mixed record, but he also laid blame on the American people, claiming that they had lost faith in their ability to solve problems.17 Even political allies felt alienated during his tenure. In January 1977, the first month of Carter’s term, Senate Majority Leader Robert C. Byrd told reporters that the President had failed to seek his advice for Cabinet appointments, raising the likelihood of confirmation battles.18 President Carter’s relationship with Congress, though productive, was often strained, much like his troubled relationship with the Georgia state legislature during his governorship.

1 https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/exploration-and-innovation/nuclear-navy.html

2 https://people.vcu.edu/~rsleeth/Rickover.html

4 https://millercenter.org/president/carter/life-before-the-presidency

5 https://www.politico.com/story/2018/11/07/this-day-in-politics-november-7-963516

6 https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/09/2016-election-1976-democratic-primary-213125/

7 https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2016/q3-4/federal_reserve

8 https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/675589

9 https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fact-sheet-the-presidents-national-energy-program

10 https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal77-1204123

12 https://millercenter.org/president/carter/domestic-affairs

13 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/shuttle-diplomacy

14 https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/enduring-peace-25-years-after-the-camp-david-accords

15 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/rapprochement-china

16 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1977-1980/china-policy

17 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/carter-crisis/