The William J. Clinton Presidential Center stands as an imposing, modern glass structure on the banks of the Arkansas River. It seems wholly out of place next to the rusting Rock Island Railroad Bridge. However, bridges are apt metaphors for the Clinton Administration, which led the United States into the 21st century. Highlighting the first American president elected after the fall of the Soviet Union, the Clinton Presidential Library illustrates how the forty-second president navigated the responsibilities of the nation’s chief executive.

Security Context

In the late 1980s, sclerotic growth and political revolutions signaled the demise of the Soviet Union. President Clinton’s predecessor, George H. W. Bush, pursued dual foreign policies of negotiating with Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev for arms control treaties while recognizing the growing influence of reformist leaders, like Boris Yeltsin.1 President Bush presided over the entry of post-Soviet republics into the international community and aided nuclear security efforts.1

Despite the collapse of America’s principal adversary, the U.S. would not relinquish its international leadership. The Bush administration led a multinational coalition in repelling Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and deposed Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega.

President Bush presided over impressive military victories, but the 1992 election focused squarely on domestic issues.2 A recession beginning in late 1990, coupled with rising anti-elitism, put President Bush insurmountably behind.2 Democratic nominee Bill Clinton convinced the electorate that he was a more capable steward of the national economy than the incumbent.

Shift in Democratic Campaigning

Poor showing in 1980, 1984, and 1988 made it clear that Democrats were out of touch with Americans.3 Clinton sought to reconcile popular, common-sense policies, like economic stimulus and tougher crime laws, with his liberal philosophy. Crime had been a powerful argument for Republicans in 1988: Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis governed Massachusetts when a criminal escaped from a prison in that state and committed a notorious rape and murder.4 Clinton applied the lessons of 1988 by offering voters support for handgun controls, larger local police forces, and reeducation programs for minor offenses.4 Voters perceived him as a responsive candidate, though he faced allegations of extramarital affairs and Vietnam draft-dodging.5

Domestic Policy

Fiscal Reform

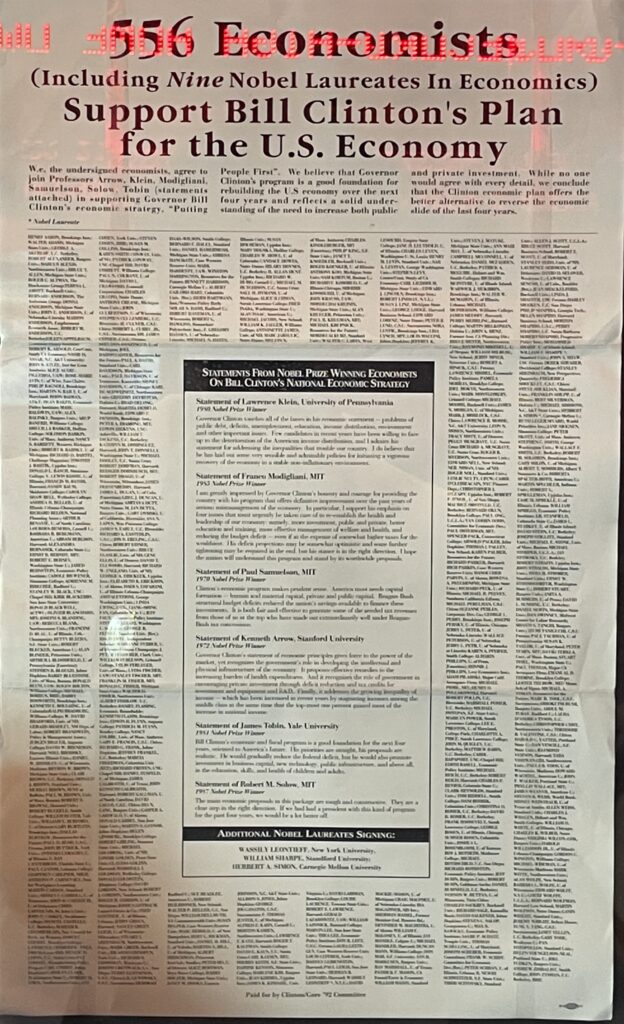

America’s public purse was under pressure in the early 1990s. The FY ’92 deficit peaked at $290B and was projected to reach $360B by 1998, an unsustainable path.6 However, due to the economy’s perceived post-recession economic weakness, Clinton’s advisors feared that aggressive deficit reduction would make another recession more likely.6 According to Alice Rivlin, OMB Director under President Clinton, the economic team agreed to cut down the deficit to $145B by FY ’96 or ’97.6 Clinton’s interest in deficit reduction surprised his campaign aides: The proposals in the campaign’s Putting People First manifesto were unworkable if the administration opted for austerity.6

The administration struggled to balance its competing economic priorities but ultimately passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1993, incorporating tax raises and spending cuts. In its September 1993 report, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the deficit would fall from $360B to $200B by 1998.7 However, the CBO cautioned that slow revenue growth and costlier welfare rolls might derail deficit reduction efforts.7

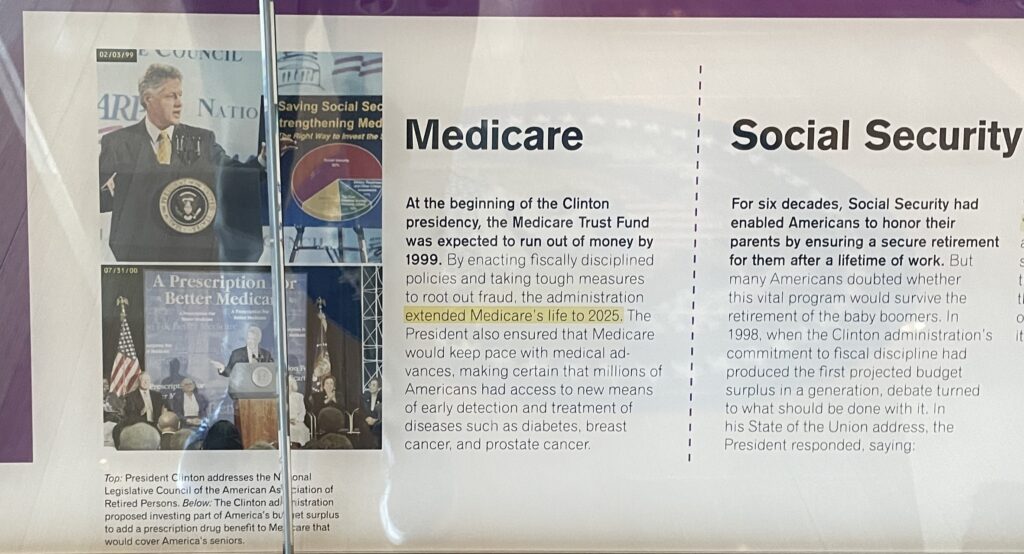

Though OBRA 1993 was an important step forward, Medicare, America’s public health insurance program for the elderly, continued to pose a formidable obstacle to balancing the federal budget. A trust fund of payroll taxes finances Medicare Part A, which pays for stays at healthcare facilities.8 Before action by Congress and President Clinton, analysts expected the Part A fund to be insufficient for projected annual expenses by 2001.8 Federal action was sorely needed to reduce the annualized 11.2% growth of Medicare expenses between 1980 and 1996.8 In 1997, President Clinton signed the Balanced Budget Act. The plan encouraged greater use of managed care rather than fee-for-service by Medicare beneficiaries.8 Medicare paid managed care organizations (e.g., HMOs) a fixed fee per beneficiary to deliver a standardized benefits package.8

Fiscal reforms and sustained economic growth throughout the 1990s helped the nation achieve a $70B budget surplus in FY ’98, nearly thirty years after the last surplus in FY ’69.9 The U.S. posted surpluses until FY ’02.10

Healthcare Reform

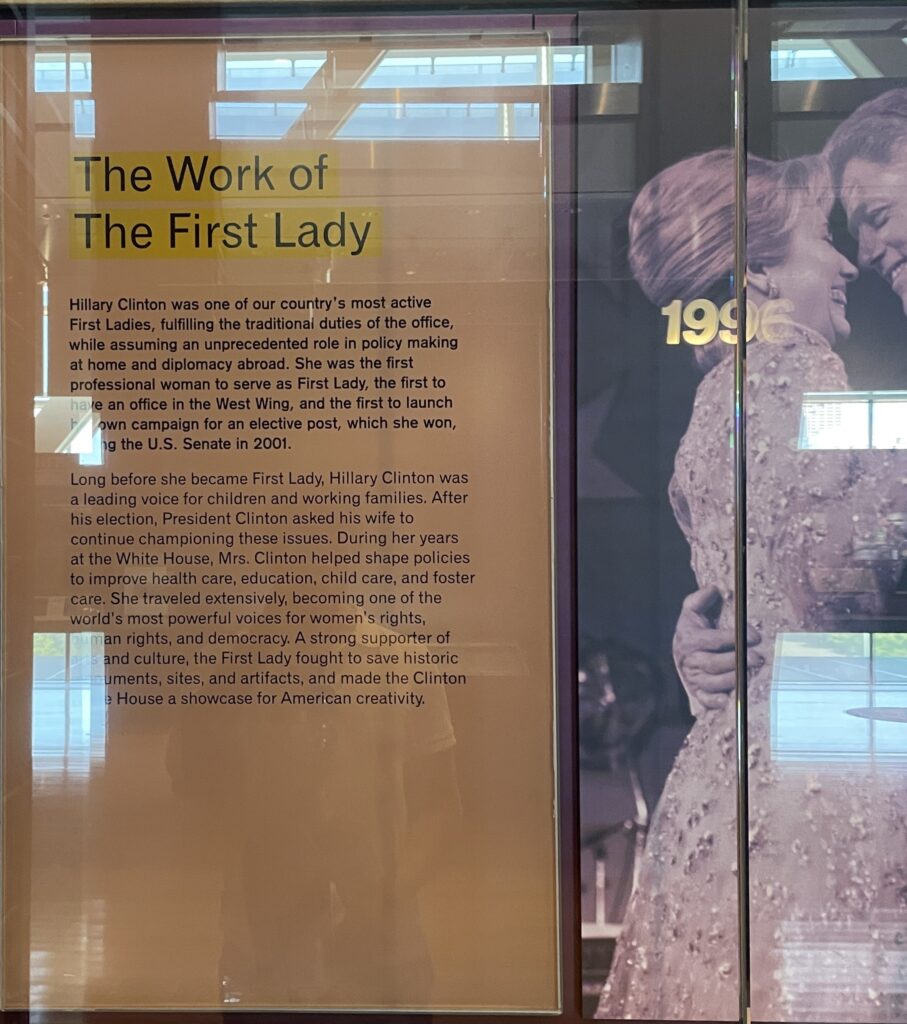

Now in office, President Clinton embarked on his most ambitious campaign promise: Comprehensive healthcare reform. Spearheaded by Mrs. Clinton, the administration’s healthcare plan created new bureaucratic agencies and mobilized the private health insurance system to achieve universal coverage (“managed competition”). Most consumers and businesses would purchase health insurance through premium-collecting regional health alliances.11 The National Health Board would regulate premiums, and a Federal Health Plan Review Board would adjudicate customer complaints.11 The federal government would also be charged with reviewing the prices of advanced new drugs.11

The healthcare plan quickly encountered resistance. On the left, progressive Democrats argued that it didn’t do enough for low-income Americans.12 On the right, Republicans were alienated by the plan’s complexity and administration rhetoric that made the plan seem like a single-payer system.12 By the autumn of 1994, the plan was dead.12

1994 Midterm Election

The Republican Party organized an impressive victory in the 1994 Congressional elections. Turnout increased dramatically from 1990, from 61 to 70 million ballots cast in House races.13 Republicans primarily benefited: In the South, the GOP vote share increased by nearly 4 million, and a significant increase was observed in the East, Midwest, and West.13 House Speaker Newt Gingrich and President Clinton sparred. Gingrich’s policies, articulated in his “Contract with America,” aimed to balance the budget through social program cuts that Clinton was unwilling to tolerate.14 The Clinton administration and Congressional Republicans failed to reach an agreement, and the government shut down in December 1995.14 The public, however, apportioned more blame to the Republicans, who attempted to keep certain sectors of the government funded through Continuing Resolutions.14

President Clinton was reelected in 1996, and Republicans maintained their majority in Congress. Relations between the White House and Congress became perceptibly frostier, however.

The Internet Age

Mature readers may remember the political furor surrounding Vice President Al Gore’s supposed claim that he “invented the Internet” (In fact, he told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer that he “took the initiative in creating the Internet.”15) The Clinton years coincided with the rapid digital interconnectivity. Computer use wasn’t novel when President Clinton was inaugurated: A February 1990 Pew Research Center poll indicated that 42% of American adults had used a computer.16 Accessing the World Wide Web, less than four years old at the time of Clinton’s inauguration, was a rarity. That changed quickly. In 1995, 14% of American adults had used the internet, and just five years later, nearly half the population had surfed the web.16 Much of the growth can be explained by demographic and technological changes. More Americans had college degrees. Browsers like Mosaic simplified Internet use.17 Nonetheless, the Clinton Administration facilitated the technology’s growth. Vice President Gore, as the Junior Senator from Tennessee, sponsored the High-Performance Computing Act of 1991, which authored the creation of the High Performance Computing and Communications Program (HPCC) in 1992.18 HPCC funded research & development efforts led by other federal agencies or the private sector.18 The Next Generation Internet Act of 1998 funded $110 million to accelerate research efforts and prepare network infrastructure to handle greater loads securely.19

Recognizing the role of the nation’s telecommunications firms in continent-wide connectivity, President Clinton signed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Congress and the administration lifted restrictions that prohibited the “Baby Bells”—regional service providers spun off from AT&T under Justice Department pressure in the 1980s—from competing in long-distance communications markets.20 The law also incentivized telecoms to upgrade their network infrastructures by allowing cable television and phone service providers to compete.20 Admittedly, there were controversies associated with the law. The 1996 Communications Decency Act, which sought to limit the transmission of online pornography, was struck down by the Supreme Court in Reno vs. ACLU as a violation of the First Amendment.21

Foreign Policy

Ethnic violence abroad and prosperity at home formed a chilling contrast. The Clinton Administration decisively shaped the outcome of three major civil conflicts. President Clinton’s successors drew on the precedents he set to chart their course through a troubled world.

Rwanda

Documents declassified in 2014 indicate an administration divided and unsure of its response to brewing communal hatred in Rwanda.22 The Rwandan Genocide claimed an estimated 800,000 lives between April and July 1994.23 How did the bloodshed begin?

Tensions between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority had defined Rwandan politics since the colonial era.24 Belgian authorities elevated the Tutsi, and a year before Rwanda became independent in 1962, the Hutu deposed the Tutsi monarch.24

In October 1990, Tutsi insurgents invaded Rwanda from Uganda.25 Negotiations began in Arusha, Tanzania, but the path to a durable peace wasn’t clear.25 Integrating government forces and rebel troops into the Rwandan Armed Forces became contentious.25 The Arusha Accords were signed in August 1993, but neither trust between the parties nor funding for the Accords’ implementation was forthcoming.25 Government soldiers were unsure about their economic future and wouldn’t receive financial support until the international community provided more funding.25 International donors were unwilling to award developmental aid until the transitional government negotiated in Arusha took power.25

By early 1994, with no economic support or transitional government in sight, Rwanda was primed for an outbreak of violence. The shootdown of Hutu President Habyarimana’s plane on April 6th engulfed the country in cataclysmic ethnic violence.25

The international community’s difficulty brokering political stability in Rwanda is excusable. Its ignorance of clear warning signs is much less so. Lt. Gen. Romeo Dallaire, the commander of U.N. forces in Rwanda, warned of Hutu extremists’ genocidal intent in January 1994.22 The cable was not shared with the U.N. Security Council, though U.S. officials were made aware.22 U.N. Ambassador Madeleine Albright received orders to lobby for withdrawing peacekeepers.22 Though the decision was reversed, the U.N. authorized a mission of just 270 peacekeepers.22 Largely given a green light by the international community, Hutu extremists presided over the worst mass murder since the Holocaust.

President Clinton’s insufficient response was motivated by general disinterest in African affairs and concern about launching a military operation during an election year.22 His predecessor launched a humanitarian intervention in Somalia in late 1992, Operation Restore Hope, to save “thousands of innocents from death.”26 Shortly into Clinton’s first term, the government’s commitment to foreign peacekeeping diminished after 18 U.S. troops were killed in Mogadishu on October 3rd, 1993.22 Every American president should avoid needlessly putting troops in harm’s way. But even simple military actions would’ve preempted genocide in Rwanda. Commander Dallaire was notified of the whereabouts of four weapons caches containing rifles and grenades transferred from the army to Hutu militias.27 Dallaire’s proposal to seize the caches was rejected.27 Had the U.N. instead chosen to act boldly, Arusha may have prevailed as Rwanda’s future. That is little consolation to the Rwandan families grieving their loved ones.

Former Yugoslavia

The fall of the Iron Curtain heralded a brighter future for Europe. In the former Yugoslavia, however, the end of communist repression brought long-simmering ethnic tensions to the fore. Tensions boiled over into violence in June 1991, when Slovenia and Croatia declared independence.28 The Yugoslav army attacked Slovenia but withdrew within weeks.28 Fighting escalated in Croatia but was stabilized in February 1992 after 14,000 U.N. peacekeepers were deployed.28 That month, Bosnia-Herzegovina declared independence.28 Bosnian Serb nationalists, bolstered by the 100,000 troops of the Yugoslav army in Bosnia, called for a separate state.28 The U.N. responded by enforcing punitive measures against Serbia, a no-fly zone over Bosnia, and an ultimatum to Serb forces besieging Sarajevo.28 The violence continued with impunity. Peacekeepers were taken hostage.28 NATO airpower protected six enclaves for Bosnian Muslims, one of which was Srebrenica.28 Srebrenica became the site of the mass murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men by Serb forces in July 1995.28

Assistant U.S. Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke was faced with the difficult task of reconciling the positions of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, Bosnia-Herzegovina President Alija Izetbegovic, and Croatian President Franjo Tudjman.29 The parties agreed to partition Bosnia into roughly equal Serb and Croat-Muslim republics.29 Under the plan, Bosnia retained one president and parliament.29 Notably, indicted Bosnian Serb war criminals were barred from holding political office.29 President Clinton dispatched 60,000 troops to enforce the November 1995 agreement, the Dayton Accords.29

Bosnia has steered clear of ethnic warfare for the past three decades. However, it remains bitterly polarized.30 Its economy is lackluster, and foreign powers, notably Russia, intervene in its affairs.30 Nonetheless, the U.S. succeeded where its European allies failed, even though the obstacles in the path of a durable settlement seemed insurmountable.

America’s involvement in the Balkans didn’t end with Dayton. Milosevic’s Serbia had been projecting control over the province of Kosovo since the late 1980s.31 The rights of Kosovar Albanians were curtailed, and the Republic of Kosovo seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991.31 The Kosovo Liberation Army began attacking Serbian authorities in 1996, triggering further repression from Belgrade.31 In 1998, the U.N. leveled sanctions against Serbia and banned arms sales.31 Despite diplomatic and military pressure from NATO military exercises, Serbia pressed on with its offensive against the KLA, persuading Secretary of State Albright to call for air strikes in September 1998.31 The next five months saw a flurry of diplomatic activity to prevent a military confrontation. Continued Serb aggression (Racak Massacre) and difficulty scoring agreement between KLA and Serb negotiators forced the start of air strikes on March 24th, 1999.31

The Kosovo War heightened the risk of a global confrontation. Russia was angered by the bombing of its historical ally Serbia.31 American planes mistakenly bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, triggering protests in China in May 1999.31 Pressure mounted on the Clinton administration to deploy ground troops in Kosovo until the announcement of a tentative peace deal put mobilization plans on hold.31 The Serbs withdrew, and 20,000 peacekeeping troops, including Russians, were stationed in Kosovo.31

U.S. intervention in Kosovo was not without its controversies. House Democrats and Republicans split on an April 28th, 1999, resolution authorizing President Clinton to launch air strikes against Serbia.31 The Kosovo War bypassed the U.N. and challenged the principle of sovereignty that governed the post-WWII order.32 Conversely, it set the principle that multilateral coalitions could intervene for oppressed peoples.32

Northern Ireland

Three decades of violence between Nationalist and Unionist factions in Northern Ireland devastated thousands of families in the troubled British region. Civil rights protests by Catholics and the forceful response from the Unionist-dominated Stormont government triggered sectarian rioting in the autumn of 1968.33 The situation deteriorated, and the British government deployed troops in August 1969.34 British forces struggled to maintain order as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) launched guerrilla attacks.35

President Clinton became involved in the conflict when he allowed the leader of the IRA’s political arm, Gerry Adams, to visit the U.S. in 1994.36 Though the decision provoked ire in the U.K., the Senators who urged Clinton to grant Adams a visa believed that it would catalyze the peace process by elevating the moderate elements of the IRA.36 The U.S.-U.K. relationship held and negotiations began in 1994 after the IRA declared a ceasefire.34

Democratic Senator George Mitchell earned the respect of the negotiators and carefully brought the Good Friday Agreement to fruition in April 1998. His firm conviction that the plan be a product of the involved parties rather than an imposed settlement is credited for the deal’s enduring success.37 It established a new, representative government in Northern Ireland, upheld equal rights, and mandated disarmament.38

Northern Ireland’s government has struggled. It was non-operational between 2022 and 2024 because of disputes arising from Brexit.39 But it remains a case of optimism. In February 2024, a Nationalist, Michelle O’Neill, was selected to lead the government for the first time in Northern Ireland’s history.39 Senator Mitchell, who sharpened his diplomatic skills working with Republican leader Bob Dole in the Senate, exemplifies the best traditions of American diplomacy.37

A Complicated Legacy

A Democratic president from humble Southern origins who pursued a modernizing agenda, Bill Clinton may inspire comparisons with Georgia’s Jimmy Carter. But Clinton’s erudition, political savvy, and notorious sex scandals differentiate him from his forebear.

In August 1994, Special Counsel Kenneth Starr replaced Robert Fiske to continue investigating allegations that Clinton benefited from illicit financial dealings during his governorship of Arkansas.40 Receiving the Attorney General’s consent, Starr expanded the investigation to include improper conduct by the Clinton Administration, including the president’s affair with Lewinsky.40 Starr suspected that Clinton had instructed his subordinates to lie under oath to the Special Counsel’s investigators.41

Did the results of Starr’s investigation justify charging the president with high crimes and misdemeanors? The House voted on October 8th, 1998, to investigate that question.41 The president apologized for his behavior but remained adamant that his conduct wasn’t criminal.41 He was impeached for perjury and obstructing justice on December 19th, 1998.41

The Senate trial began on January 14th, 1999, with a three-day opening statement from the thirteen House impeachment managers.41 He was acquitted on both articles on February 12th, following a controversy about whether to gather witness testimony.41

Regardless of the legality of Clinton’s behavior, his legacy forever remains tarnished by his sexual indiscretion. (Monica Lewinsky was not the only woman to allege the president’s sexual misconduct.) The public recognized his leadership ability, giving him a nearly 70% approval rating in January 1998.42 Two-thirds of Americans favored Clinton remaining in office.42 Future leaders should interpret Clinton’s legacy cautiously. His numerous policy victories deserve recognition. But his political success did not permit him to ride roughshod over others.

1 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1989-1992/collapse-soviet-union

3 https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal84-856-25733-1150749

5 https://millercenter.org/president/clinton/campaigns-and-elections

6 https://millercenter.org/issues-policy/economics/deficit-reduction-in-bill-clinton-s-first-budget

8 https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/97-802.html

9 https://clintonwhitehouse4.archives.gov/WH/New/html/19981028-13004.html

10 https://www.concordcoalition.org/blogs/looking-back-20-years-at-the-1997-balanced-budget-agreement/

12 https://www.princeton.edu/~starr/20starr.html

13 https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal94-1102765

14 https://millercenter.org/1995-96-government-shutdown

15 https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/stories/1999/03/09/president.2000/transcript.gore/

17 https://www.elon.edu/u/imagining/time-capsule/150-years/back-1960-1990/

18 https://www.nitrd.gov/legislation/

19 https://usinfo.org/usia/usinfo.state.gov/usa/infousa/tech/gii/nii.htm

21 https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/telecommunications-act-of-1996/

22 https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/05/rwanda-revisited-genocide-united-states-state-department/

23 https://www.britannica.com/event/Rwanda-genocide-of-1994

24 https://www.history.com/topics/africa/rwandan-genocide

25 https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB469/

27 https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/mar/30/historybooks.features11

28 https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/specials/bosnia/context/apchrono.html

31 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/kosovo/etc/cron.html

32 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/kosovo/procon/kitfield.html

33 https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch68.htm

35 https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-49250284

36 https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-46621642

37 https://hbr.org/2015/06/george-mitchell

38 https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-61968177

39 https://www.npr.org/2024/02/03/1228844747/northern-ireland-sinn-fein-michelle-oneill-government

40 https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/counsel/office/other.html

41 https://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/history/johnson/clintontimeline.htm

42 https://www.aei.org/articles/performance-trumps-character/