Author’s Note: I did not make a punctuation mistake when I omitted the period from the “S”! President Truman’s parents were unsure whether his middle name should be Shipp or Solomon, so they compromised with the letter S!

Independence, Missouri, the birthplace of President Harry Truman, lies not far from Kansas City, the place that would define his entry to national politics. The sleepy community surrounding the Harry S Truman Presidential Library contrasts sharply with the tumult that Vice President Truman unexpectedly inherited following the death of President Roosevelt in 1945.

As the introductory video at the library emphasized, President Truman immediately faced questions about his competence to lead a newly minted albeit exhausted superpower at the end of WWII. His responses to the nation’s foreign and domestic crises set the tone for the emergent Cold War involving renewed hostilities between the United States and the Soviet Union, its wartime ally. President Truman has earned his place as a visionary and transformative president.

Early Life

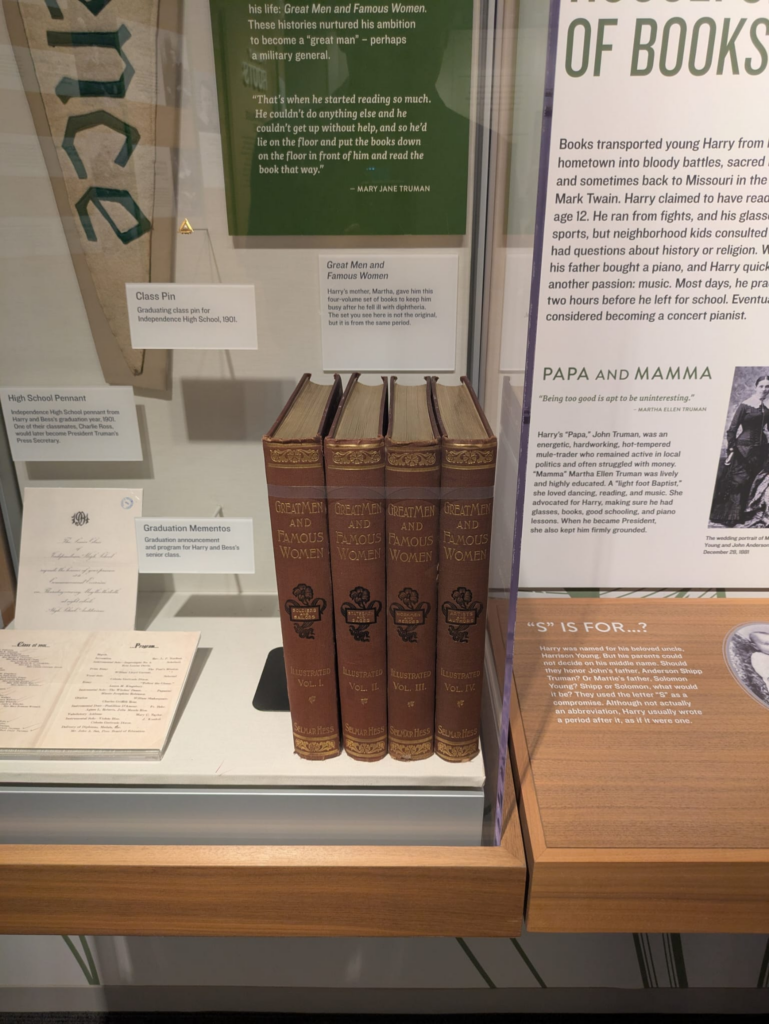

Harry S Truman was a bookworm and avid pianist. His mother, a highly educated and supportive woman, furnished him with the four-volume set Great Men and Famous Women after he fell ill with diphtheria. Truman’s mother also helped him discover his aptitude for piano, which he practiced religiously before school.

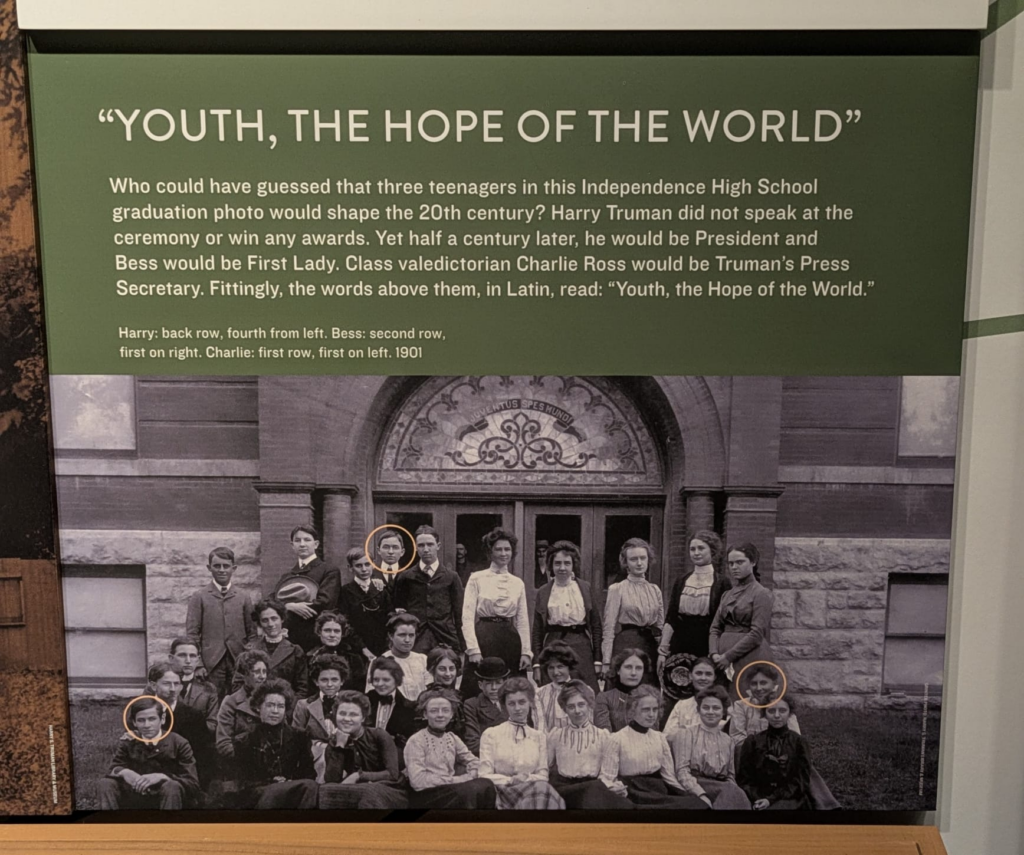

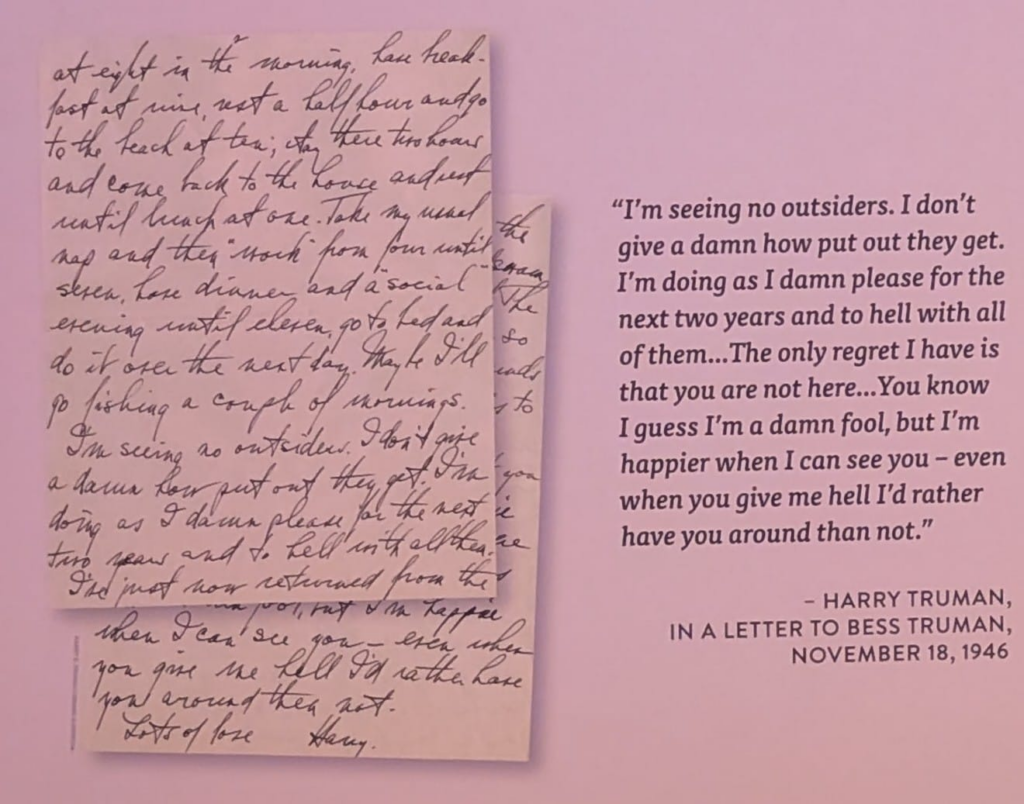

Independence also introduced Truman to his future wife, Elizabeth “Bess” Wallace. Unlike her husband, Bess’ family was prominent, and she was a superb athlete.

After graduating from Independence High School in 1901, Truman sought entry to West Point, which he was denied because of his poor eyesight. His chance to serve would come in 1905, when the Missouri National Guard admitted him.

The Truman family went to Kansas City after going bankrupt due to poor investment decisions made by Truman’s father. Truman quickly demonstrated his work ethic to his employers.

Truman left the city to help his father and brother manage his grandmother’s Grandview Farm. Truman assumed responsibility for the farm in 1914, after his father passed away. He also inherited his father’s responsibility as road overseer, his first introduction to public life.

After America entered WWI, Truman left the farm to train at Camp Doniphan in Oklahoma. His leadership ability resulted in a promotion to captain. He led an Artillery Unit that deployed to France in 1918.

After the war, Truman founded a men’s clothing store with Eddie Jacobson, a friend from the Army. The venture floundered after a recession swept the country in 1920. That provided an opportunity for Jim and Mike Pendergast of the eponymous Pendergast political machine to recruit Truman as their candidate for the Eastern Jackson County Judge. The Pendergast family dominated the working-class base of Kansas City, dispensing patronage for votes.

National Politics

From county judge, Truman leapfrogged into the Senate in 1934. He won on the simple promise of doggedly backing President Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. In the Senate, Truman generally kept a low profile, earning the nickname “go-along, get-along Harry.”

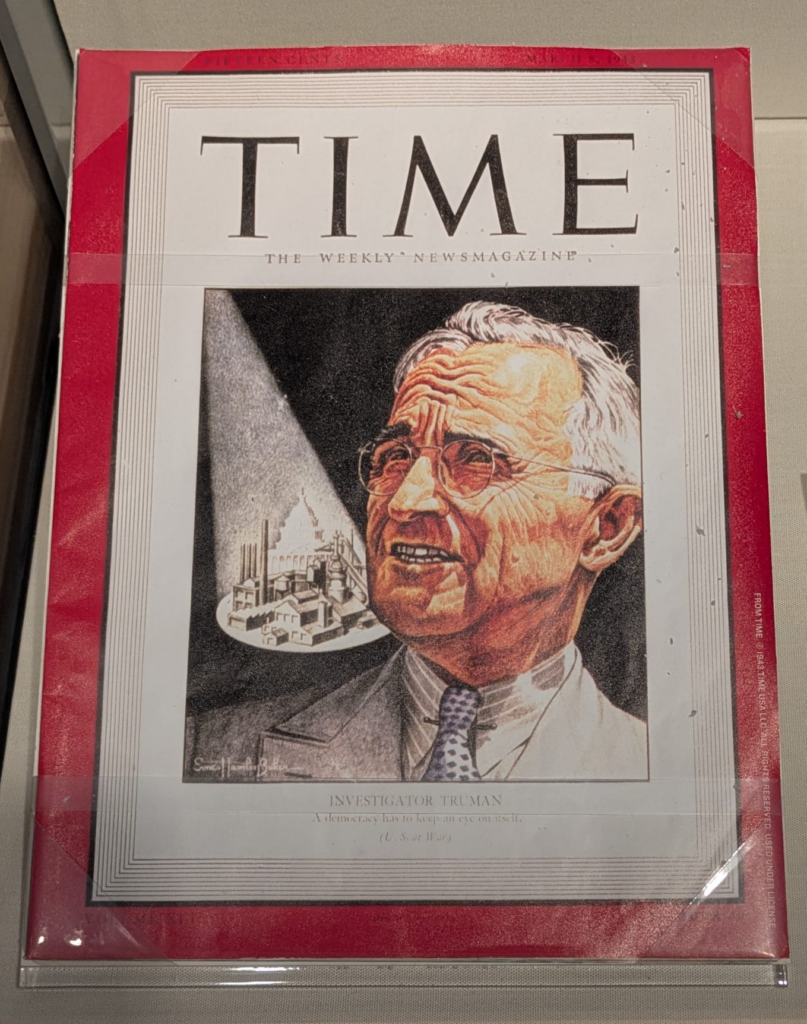

Tensions in Europe boiled over with the German invasion of France and the Low Countries in 1940. Though America was officially “neutral,” President Roosevelt ordered national defense preparedness. Senator Truman was concerned that defense grants were being distributed unfairly, disadvantaging small business owners. He sponsored Senate Resolution 71, which created the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. Later known as the Truman Committee, it carefully investigated allegations of profiteering and attracted broad media coverage. Though Truman was loyal to Roosevelt’s Democratic administration, he pointed out failures in defense planning that emanated from the White House.1

At the Democratic convention in July 1944, Senator Truman was adamant that he didn’t want to be Vice President. That was until he learned the seriousness with which the party’s leadership wanted his name next to Roosevelt’s on the ballot: They perceived incumbent Henry Wallace as too liberal. At the final vote count, Truman defeated Wallace 1000-926.2

His Own Mark

Ending the War

Vice President Truman had served less than three months in his office when President Roosevelt passed away on April 12th, 1945. Shortly after, German forces surrendered, marking the end of the war in Europe. President Truman met with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin at the Potsdam Conference, which dealt primarily with Germany’s future.3

The Truman cabinet didn’t have a consensus about how to deal with Germany. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau called for the dismemberment of Germany into agricultural states, while Secretary of War Henry Stimson believed that a strong, democratic Germany would better serve Western European interests. Truman sided with Stimson.

At Potsdam, Stalin expected Truman to maintain the position that Roosevelt had taken: Germany would be expected to pay large war reparations, half of which would be sent to the Soviet Union. Truman, however, was concerned that burdensome war reparations would replicate the circumstances that resulted in Nazism.4

Though the wartime allies didn’t agree on reparations, they agreed to disarm, demilitarize, and occupy Germany in four zones. Post-war Germany would be forbidden from possessing armed forces, Nazi-era racial laws would be repealed, and German war criminals would be tried. Controversially, the Allies allowed Poland to deport Germans in territories it had acquired to compensate for territories it had lost in the east to the Soviet Union. During negotiations, Truman hoped to play America’s possession of nuclear weapons as his trump card; however, Stalin already knew, and he didn’t concede easily.4

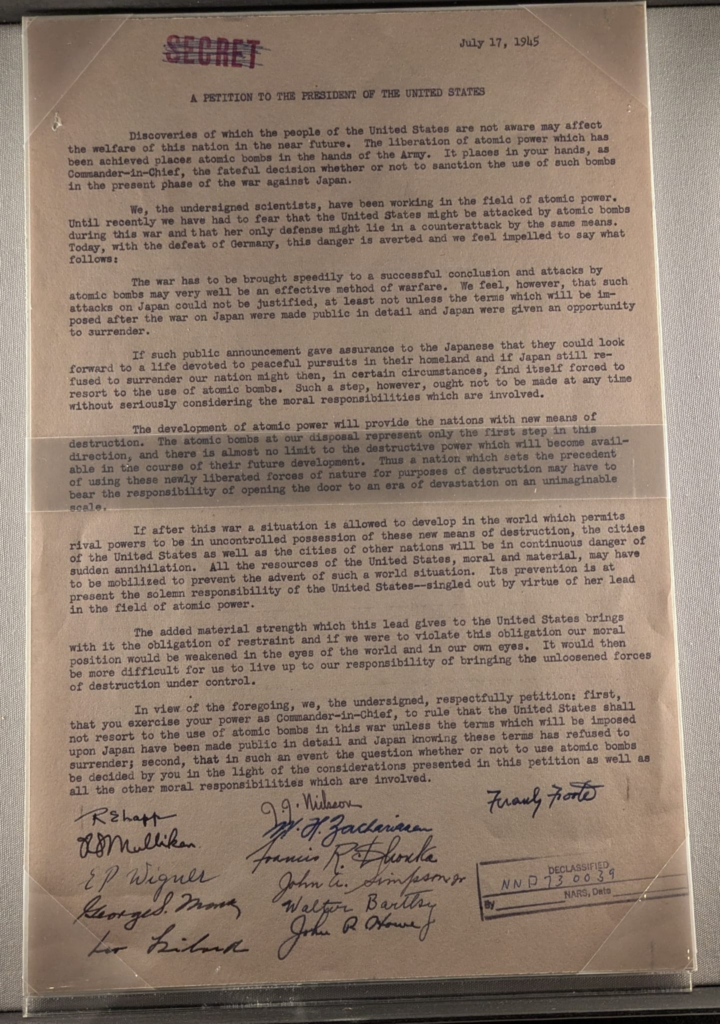

President Truman was informed of America’s nuclear weapons program and was presented with the dilemma of whether to use it to defeat Japan. In May 1945, Secretary of War Henry Stimson convened the nuclear scientists, military generals, and industrialists involved with the Manhattan Project (known as the “Interim Committee”) to determine the best use of atomic weapons. On June 21st, 1945, the Interim Committee concluded that the atomic bomb would be dropped on a war plant in the vicinity of other buildings. Generals Leslie Groves and Thomas Farrell presented Kokura, Hiroshima, Niigata, and Kyoto as potential targets. Kyoto would be replaced with Nagasaki in the final list that was presented to President Truman.5 In his decision to use the atomic bomb, President Truman considered the terrifying casualties sustained at Okinawa: 12,000 Americans, 100,000 Japanese, and 100,000 Okinawans died over ten weeks to seize one small island. Though Japan was weakened considerably, it still retained a massive force to defend the homeland.6 On August 6th, 1945, the Enola Gay B-29 bomber dropped the Little Boy atomic weapon on Hiroshima, instantly killing those in the vicinity and hundreds of thousands more over the following years due to radiation sickness.7 On August 9th, a second weapon with greater yield (Fat Man) was dropped on Nagasaki. Though Fat Man was a more powerful weapon, it had a smaller death toll, due to the geographical characteristics of Nagasaki and the inaccurate targeting of the weapon due to weather.8 Truman did not need to reauthorize military leaders to release the second weapon; his initial authorization was applicable to the entire list of four targets.6

Demobilizing the Country

Transitioning the country from wartime footing was a formidable task. Demobilized soldiers wanted back their jobs that had been filled by women and minorities. An acute housing crisis emerged, too, resulting in mass homelessness. President Truman ended wartime wage and price controls in 1946, fueling inflation. Truman’s 21-point economic program met stern resistance from Republicans and conservative Democrats. In the face of seeming government paralysis, Americans backed Republicans in the 1946 midterms. (One of the Republicans elected in 1946, Richard Nixon, would go on to become president.)

GI Bill

The Servicemembers’ Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the GI Bill of Rights, continues to benefit Americans today. Support for it is bipartisan, but that wasn’t always the case. Congress’ goal was to do a better job assimilating veterans than it did after WWI. The lack of support provided to WWI veterans resulted in a march on Washington in summer 1932. After the first draft of the GI Bill was introduced in January 1944, a bitter debate emerged between the House and the Senate on whether to provide unemployment benefits, which some argued would disincentivize veterans from looking for work. After a pivotal tie-breaking vote, the bill appeared on President Roosevelt’s desk. The Department of Veterans Affairs was authorized to provide veterans financial support for college education and vocational training, loans, and unemployment payments.16

Labor Relations

The Republican Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act, which curbed unions’ political power and allowed the president to seek injunctions to compel striking workers back to work. Truman’s opposition to Taft-Hartley allowed him to regain some of the support he lost with labor, a key Democratic constituency. Truman clashed with other Republican policies, like raising tariffs on wool.9

Despite his stated support for organized labor, Truman mounted a heavy-handed response to the steel strike of 1952. To fund the Korean war without imposing significant hardship on war-weary Americans, the government established the Office of Price Stabilization (OPS) to set price controls on war-related industries, and the Wage Stabilization Board (WSB) to limit wage rises. Consequently, the powerful steel unions launched a strike. As negotiations faltered between the OPS and steel companies (the steel companies wanted to charge the government more to meet the unions’ demands), President Truman seized control of the steel industry in April 1952.10 In Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer, the Supreme Court ruled against Truman.11

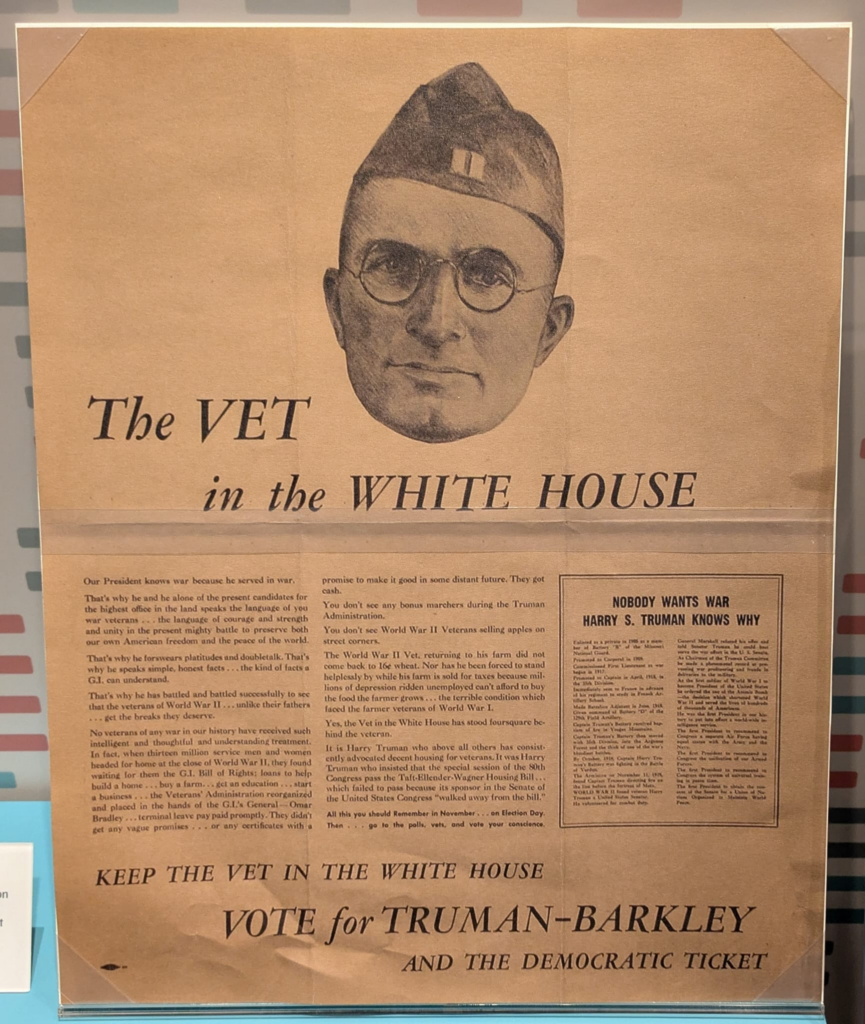

Reelection 1948

Truman’s victory in 1948 was far from guaranteed. America’s post-war economic challenges and uncertainty in its foreign relations made him appear unfit for office. His Democratic base seemed to be falling apart: Southern Democrats were angered by his backing of civil rights, while progressives believed he was overly hostile to the Soviet Union. Though he didn’t win the popular vote (the Southerners ran a third-party candidate, Strom Thurmond), he commanded enough support in the New Deal base to win another four years in the White House.12

Domestic Policy

Cold War Domestic Spillover

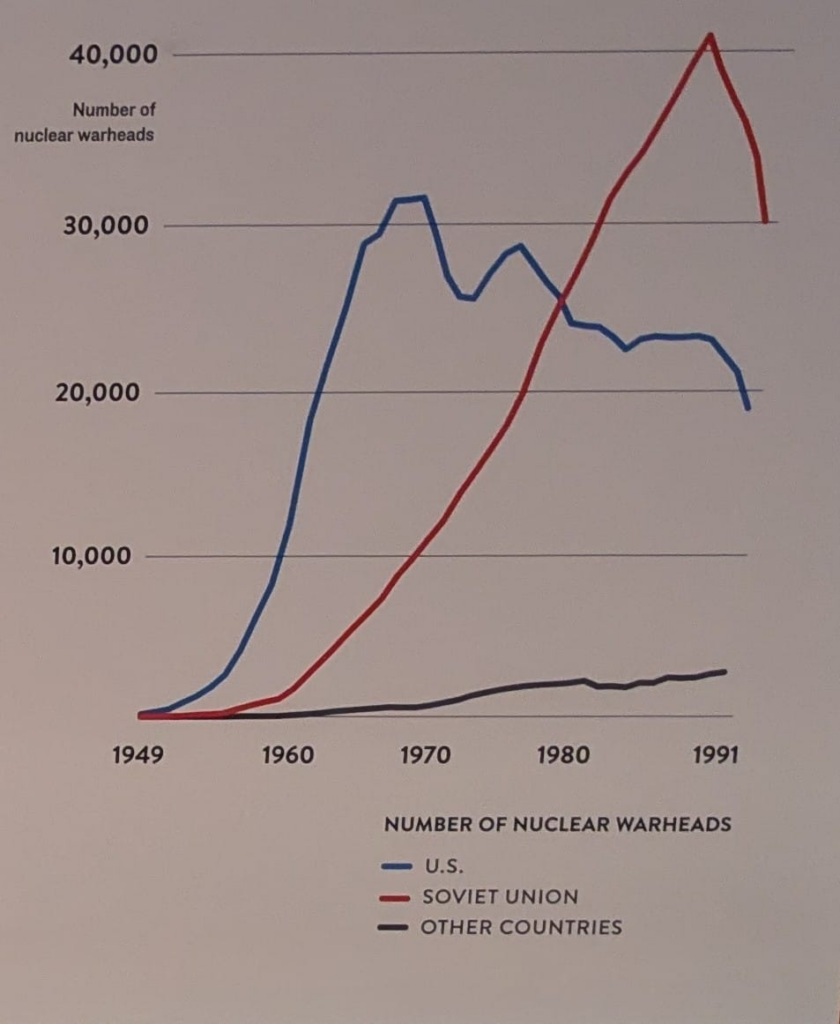

In 1949, the Soviets conducted a test of “First Lightning,” its first nuclear weapon, starting the arms race that would define the Cold War until its conclusion in 1991. Americans’ anxiety about the Soviet possession of nuclear arms was compounded by revelations that American spies helped them. British and American intelligence agencies countered the threat of espionage with the Venona program, which revealed that Manhattan Project physicist Karl Fuchs had shared classified information with the Soviets. Other prominent spies included Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were executed in 1953.

Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy exploited Americans’ concerns. In a 1950 speech, he claimed that the State Department was “infested with Communists.” McCarthy’s crusades lasted until 1954, when he was censored by the Senate for his baseless accusations.13

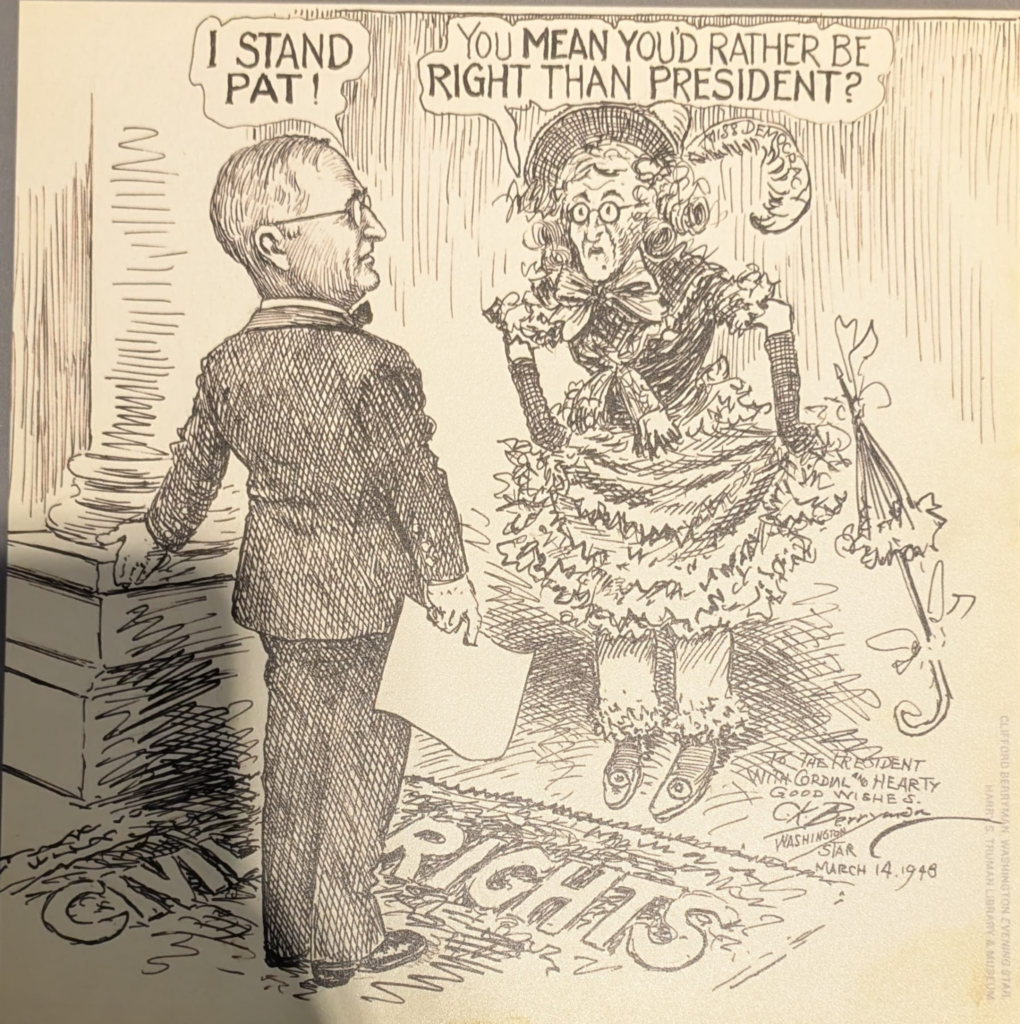

Civil Rights

Civil rights proved a major political challenge for any midcentury Democratic presidential aspirant. The powerful and conservative Southern wing of the party could derail any legislative program that sought to correct racial injustice.

President Truman was not a natural supporter of civil rights. He made racist comments and opposed civil rights demonstrations. Thus, his use of executive office to make overtures to Black Americans caught many off-guard. He sought to eliminate prejudicial hiring for federal jobs through Executive Order 9980, and, most notably, desegregated the armed forces through Executive Order 9981. Truman’s legacy on civil rights remains complicated due to comments he made following his presidency. He claimed that lunch counter sit-ins were organized by Communists, drawing a stern rebuke from Martin Luther King Jr., who had previously been his supporter.14

The Fair Deal

Truman sought to advance the New Deal agenda of his predecessor. He proposed new public works programs, a rise in the minimum wage, an expansion of Social Security, and a national health insurance system.9 The only legislation that passed was the Employment Act of 1946, which created the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) and called for the government to maintain economic stability through Keynesian economics.15

Foreign Policy

Marshall Plan

At the end of WWII, the Soviet Union’s intent to continue its occupation of Eastern Europe became increasingly clear. President Truman recognized that offering aid to war-torn European countries would stymie the Soviet threat, facilitate democratic governance, and provide trade opportunities for Americans. Secretary of State George Marshall articulated what would become the Economic Cooperation Act at his Harvard commencement speech. The Economic Cooperation Act of 1948, more commonly known as the Marshall Plan, included $12 billion worth of funding to rebuild Western Europe. Though the economic merits of the plan are still debated, it provided a basis for America’s successful foreign aid programs.17

The Marshall Plan was an application of the Truman Doctrine, which stipulated that the US would support democratic nations facing a threat through military and economic assistance. It was a break with the longstanding US policy of non-intervention. President Truman first applied his Doctrine to support Greece and Turkey, which had been receiving aid from Britain. Notably, the Truman Administration justified intervention on the basis that the Soviets were backing the Greek Communist Party, even though Stalin had refused to provide support to the Greek communists.18

Future of Germany & Standoff in Berlin

Allied forces occupied and partitioned Germany at the end of WWII. Berlin posed a unique challenge because it was located deep in Soviet-controlled territory but was occupied by American, British, French, and Soviet troops. The Soviets attempted to assert their dominance of the city in June 1948 by blockading the Western-controlled sectors. For nearly a year, Allied aircraft defied the blockade and brought critical supplies to Berliners.19

In 1946, Britain and America merged their sectors of occupied Germany, with France eventually following suit. Western authorities began rebuilding their portions of Germany, aiming to restore German economic independence. The Western approach differed greatly from the Soviet administration of eastern Germany, which dismantled the region’s industry to prevent it from becoming a threat.20

Western governments doubled down on their efforts to rebuild and unify the portions of Germany under their control, introducing the Deutschmark in 1948 without notifying the Soviets. The new currency made Germany eligible for Marshall Plan aid. When the Berlin Airlift began, the Soviets offered to lower their blockade if the Deutschmark was retracted from West Berlin.19

Berliners’ resilience ensured that Western support for the city was forthcoming. 300,000 residents marched to the Reichstag to oppose Soviet domination after Communist organizations forced the Berlin City Council to adjourn.19 Berlin, which just a few years prior menaced Europe, was now a critical front in the Cold War.

Creation of the United Nations

In June 1945, with war in the Pacific still raging, representatives of 50 nations gathered in San Francisco to sign the United Nations Charter. The US Senate ratified the Charter in October 1945, granting it legitimacy and achieving the vision that President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill first articulated in the Atlantic Charter of 1941.21

Much of the groundwork for the UN was laid at wartime conferences among the Allies. President Roosevelt and Soviet Premier Stalin discussed a role for “the four policemen”—the US, Britain, Soviet Union, and China—to enforce global peace. The policemen would be accompanied by a global forum to discuss economic and social issues. A set of organizations would handle specific areas of transnational cooperation, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization and the International Civil Aviation Organization.22

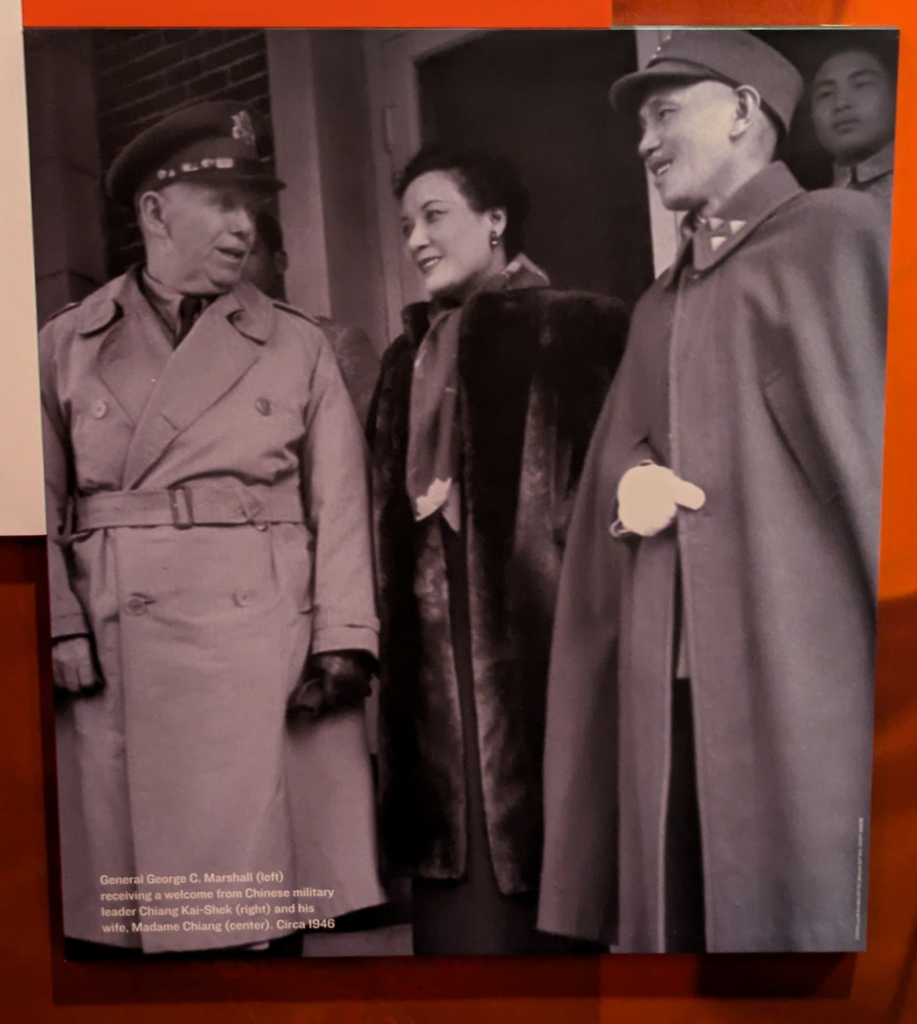

China

Since the early 1920s, two factions battled for control of China: The Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong, and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), led by Chiang Kai-Shek. The lack of progress on a negotiated end to the conflict frustrated Ambassador Patrick Hurley, who resigned. President Truman asked General Marshall, who had been stationed in the country from 1924-1927, to continue peace negotiations. His task was not an easy one: Both Chiang and Mao were stubborn negotiators. Chiang knew he had the backing of the U.S., regardless of the outcome of negotiations, so he had little reason to compromise; Mao felt similarly confident about the Soviet Union’s support. Marshall was unsuccessful and returned to the US a year after he was dispatched.23

The Truman Administration did not see the Kuomintang as a major strategic asset and believed that only the Chinese people could settle the civil war. The Communists enjoyed broader popular support due to the Nationalists’ dictatorial behavior and corruption. Consequently, they prevailed militarily, and the Nationalists fled to Taiwan. The U.S. would recognize Taiwan as China’s legitimate government until the 1970s.24

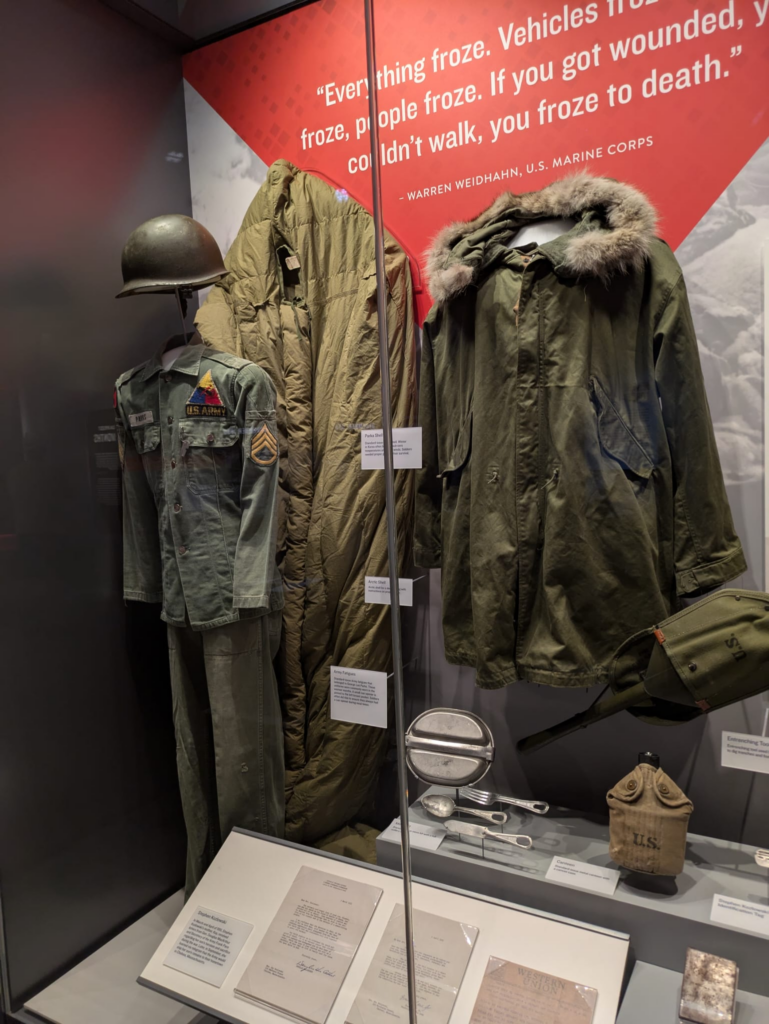

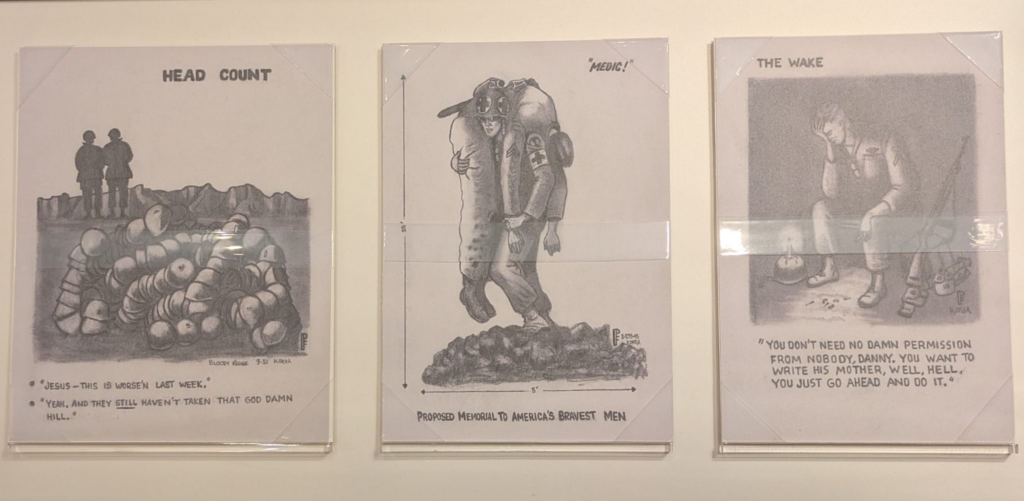

Korea

On June 24th, 1950, North Korean Forces under Kim Il-sung invaded South Korea with backing from the Soviet Union. Truman provided materiel to the South Koreans and urged the United Nations to seek a resolution. Because the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council, the body could demand a ceasefire and marshal aid for South Korea. Domestically, President Truman circumvented Congress by categorizing America’s military response as a contribution to a UN “police action.”25

UN forces led by General Douglas MacArthur initially suffered major setbacks, partially due to a post-WWII reduction in defense spending.26 The Inchon Offensive, an amphibious assault conducted deep within North Korean-held territory, helped the US-led coalition turn the tide. Inchon resulted in the liberation of South Korean capital Seoul and severed North Korean supply lines, allowing UN forces to advance north of the 38th parallel.27

The triumph at Inchon would soon be met by a major setback: The surprise arrival of Chinese troops. Between 10,000 and 20,000 troops massed outside Unsan and inflicted major casualties on UN forces in late-October 1950.29 The conflict grinded to a stalemate at the 38th parallel.

The deteriorating military situation led to a rift between Gen. MacArthur and President Truman. MacArthur hoped to liberate North Korea from communism, while Truman aimed to prevent South Korea from being overrun. MacArthur proposed opening a front with China and refused to obey Truman, ordering his troops past the 38th parallel and jeopardizing Truman’s ceasefire negotiations. In a controversial move, Truman suspended Gen. MacArthur in April 1951. Though many Americans were angered by Truman’s decision, they ultimately recognized that the General’s positions were extreme and risked starting a nuclear WWIII.28

The Korean War would only see its final resolution in the administration of Dwight Eisenhower after claiming 33,000 American lives over three years.26

Recognition of Israel

President Truman’s decision to recognize Israel in May 1948 came as a surprise. The US supported UN Resolution 181, which called for the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. However, the State Department warned against granting statehood, believing that it would encourage the Arab world to lean closer to the Soviet Union and heighten the risk of sectarian conflict in the troubled region.30

The forces that contributed to Israeli statehood had long been in the making. British Foreign Minister Lord Arthur Balfour declared his government’s support for a Jewish state in Palestine in 1917. Shortly afterward, Britain and France secretly partitioned former Ottoman territories and obtained colonial mandates from the League of Nations. The territories including mandatory Palestine fell under British rule. As Jewish immigration to Palestine increased, sectarian violence grew. After the Arab revolt of 1936-1939, Britain sought to restrict Jewish immigration to Palestine, which angered Zionists, who had helped the British suppress the Arab revolt.31

In November 1947, the UN passed Resolution 181, which put Jerusalem, of religious significance to both Muslims and Jews, under UN control. This provision angered Arab Palestinians, and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948 broke out shortly after Israel proclaimed independence on May 14th, 1948. The US enforced an arms embargo against all parties.32

Conclusion

Harry Truman’s rise to political prominence was marked by accusations that he had only achieved high political office through intervention from the Pendergasts. However, President Truman left a distinctive mark on American politics, reimagining America’s role in the world as a benevolent superpower and helping his countrymen accept their new worldly responsibilities. Truman lacked the academic, commercial, or military distinguishments of other presidents; what he lacked in ability he more than made up for in his simple, relatable demeanor and unabashed support for New Deal policies.

References

1 https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/investigations/truman.htm

2 https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/the-missouri-compromise/

4 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/potsdam-conf

5 https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/debate.htm

6 https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/potsdam_decision.htm

7 https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/hiroshima.htm

8 https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/nagasaki.htm

9 https://millercenter.org/president/truman/domestic-affairs

10 https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/steel-strike-1952

11 https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/343us579

12 https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/election-1948

14 https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/truman-harry-s

15 https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/employment-act

16 https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/gi-bill.pdf

17 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/marshall-plan

18 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/truman-doctrine

19 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/berlin-airlift

20 https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/cwr/107189.htm

21 https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/wwii-80-united-nations/

22 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/un

23 https://www.cia.gov/resources/csi/static/Article-George-C-Marshall-Mission-to-China-1945-47.pdf

24 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/chinese-rev

25 https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/united-nations-korea

26 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Harry-S-Truman/Cabinet-of-President-Harry-S-Truman

28 https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/firing-macarthur

30 https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/creation-israel