Author’s Note: Between January and April 2025, I lived in Texas to complete a co-op term with ExxonMobil. College Station, the home of Texas A&M, where the George H. W. Bush library has stood since 1997, was roughly three hours from my apartment in Beaumont. I embarked on the journey with my mother early on a Saturday morning in late March. We drove most of the one hundred and sixty miles along winding, single-lane Farm to Market roads that snaked through the Sam Houston State Park, a breathtaking national treasure. I can only imagine the exhilaration the Connecticut-born fortieth president felt driving his red Studebaker to start a new life in the Lone Star State!

George Herbert Walker Bush, a seasoned public servant, was ideally suited for the circumstances he inherited as president. The Soviet Union was tottering, marking the triumph of liberal democracy over totalitarianism and inspiring hope that the people of Eastern Europe and Central Asia could experience long-awaited freedom. However, the fall of the U.S.S.R. brought risks, which President Bush, with his extensive diplomatic skill, mitigated deftly. New threats to the world order emerged from ambitious despots in the late 1980s and early 1990s, portending today’s might-makes-right world. International relations coursework still highlights President Bush’s approach towards troublesome regional powers.

Though President Bush is most remembered for his contributions to American foreign policy, he corralled major domestic legislative achievements through Congress. His domestic and foreign policies were motivated by a lifelong commitment to service, which he inherited from his parents and demonstrated from a young age. The historical record should not gloss over his support for Goldwaterism in his first run for national office, however.

Formative Years

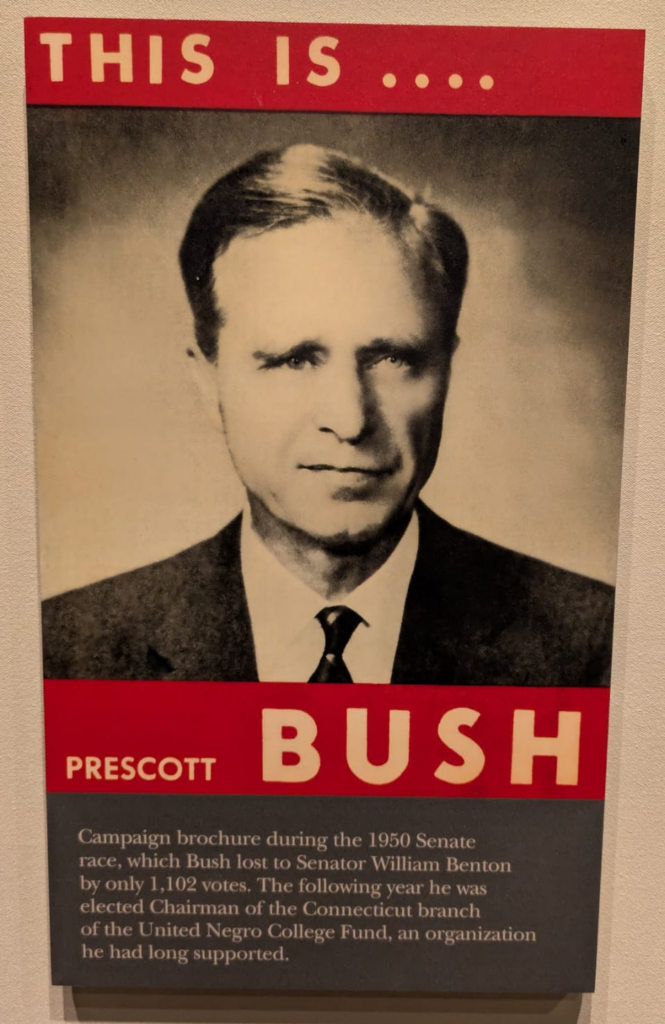

Family influences decisively shaped the president’s life trajectory. His father, Prescott Bush, an imposing, athletic man of six feet seven inches, served as the Senator from Connecticut. Notably, his father’s support for civil rights, including his leadership of the Connecticut branch of the United Negro College Fund, differed from the Goldwaterite position he would take during his first Senate run.

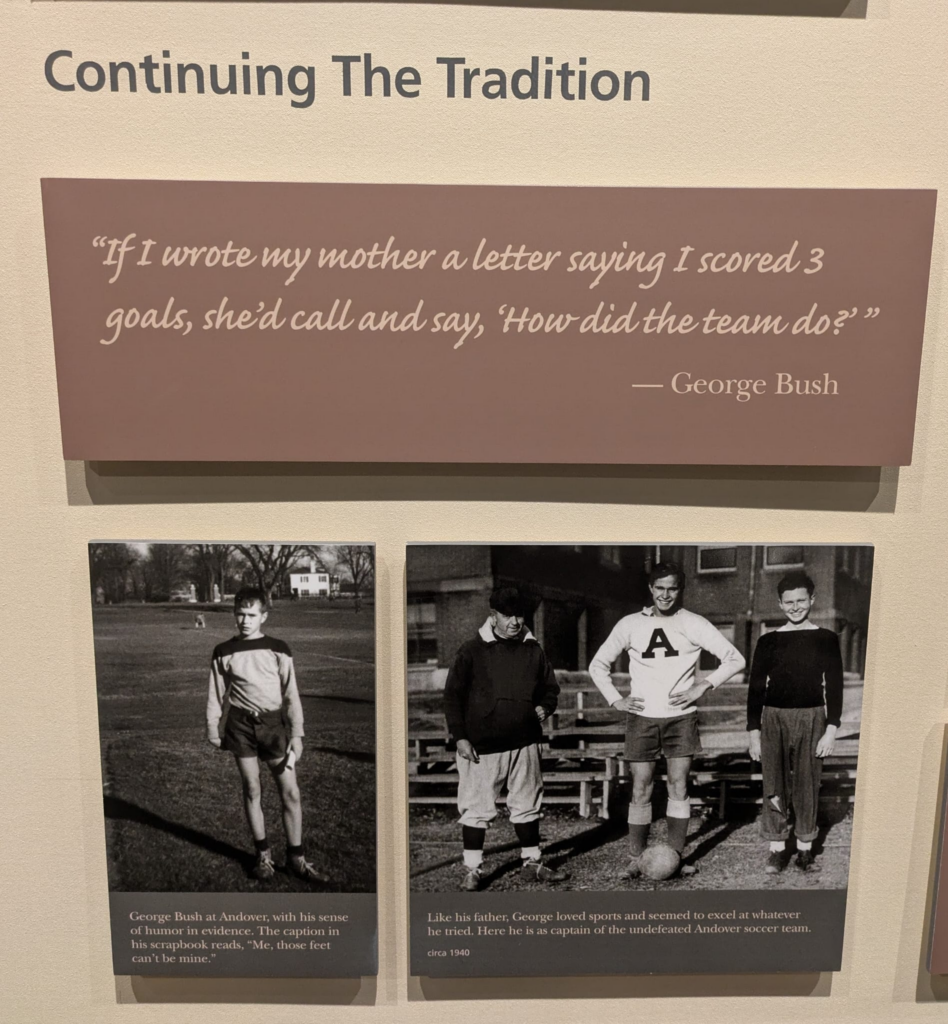

The president’s mother, Dorothy, a talented athlete, influenced her son’s early affinity for team sports. She inadvertently encouraged the multilateral instincts that would make President Bush’s diplomacy successful.

America’s entry into World War II directed the president towards naval aviation. Enlisting on his 18th birthday, he became one of the youngest pilots. An attack on his Grumman TBM Avenger in the Pacific, which left his crewmates dead, convinced him that he had a higher purpose to serve.

Early Career & 1964 Senate Run

After serving in WWII and graduating from Yale, Bush married Barbara Bush, whom he had been dating since the age of 17. The young couple (including their son George) relocated to Texas. As biographer Jon Meacham notes, Bush hoped to be far enough away to build his career outside his father’s shadow while close enough to leverage his father’s connections.

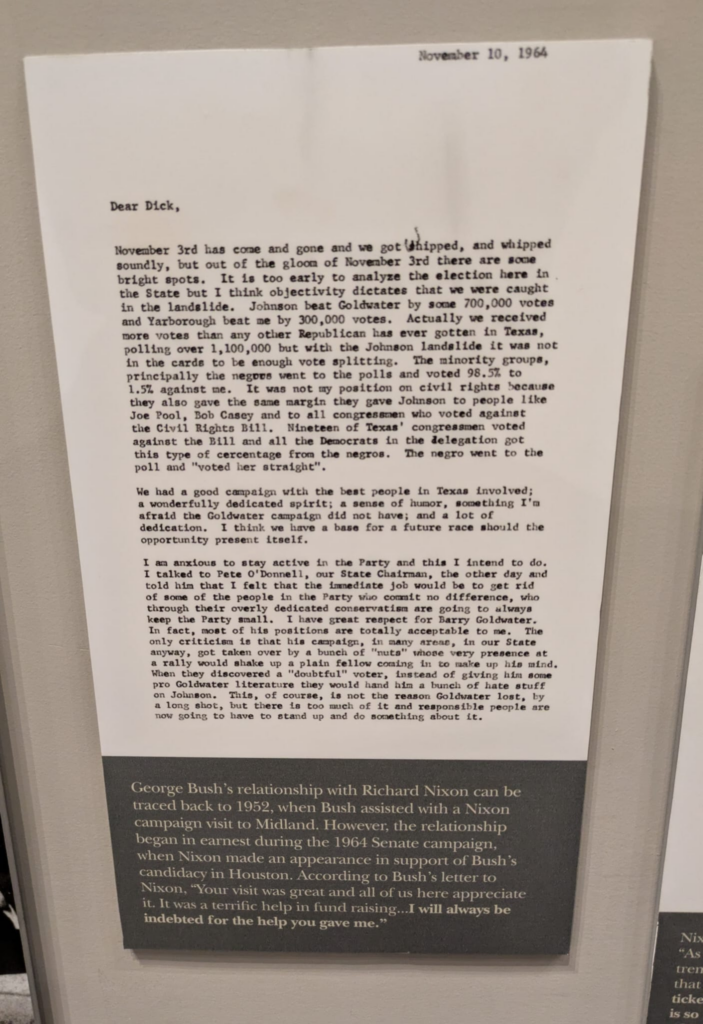

In Texas, Bush founded the Zapata Petroleum Company, which specialized in offshore oil drilling. Zapata’s commercial success elevated Bush’s profile, who ran for Senate in 1964 against Ralph Yarborough. Aligning himself closely with right-wing civil rights opponent Barry Goldwater, Bush was soundly defeated, just as Lyndon Johnson handily dispensed of Goldwater. In a letter to Richard Nixon, Bush claimed that it wasn’t Goldwaterite positions that doomed his campaign, but rather that “nuts” were partially responsible for alienating voters.

Political Rise

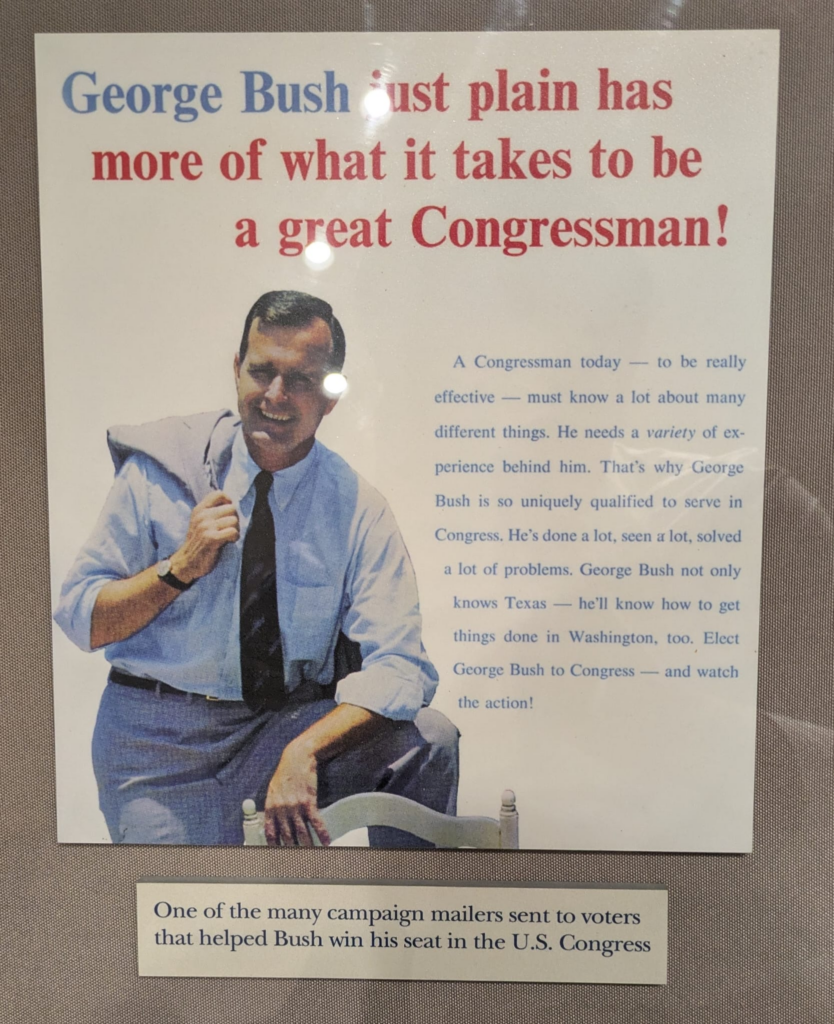

Armed with greater political savvy, Bush successfully ran for Congress in 1966. Earning a seat on the powerful Ways and Means Committee and supporting parts of President Johnson’s Great Society initiatives, Bush established a reputation as a moderate conservative. He attempted to run for Senate in 1970, but instead of facing the liberal Yarborough, he faced conservative Lloyd Bentsen, to whom he lost.

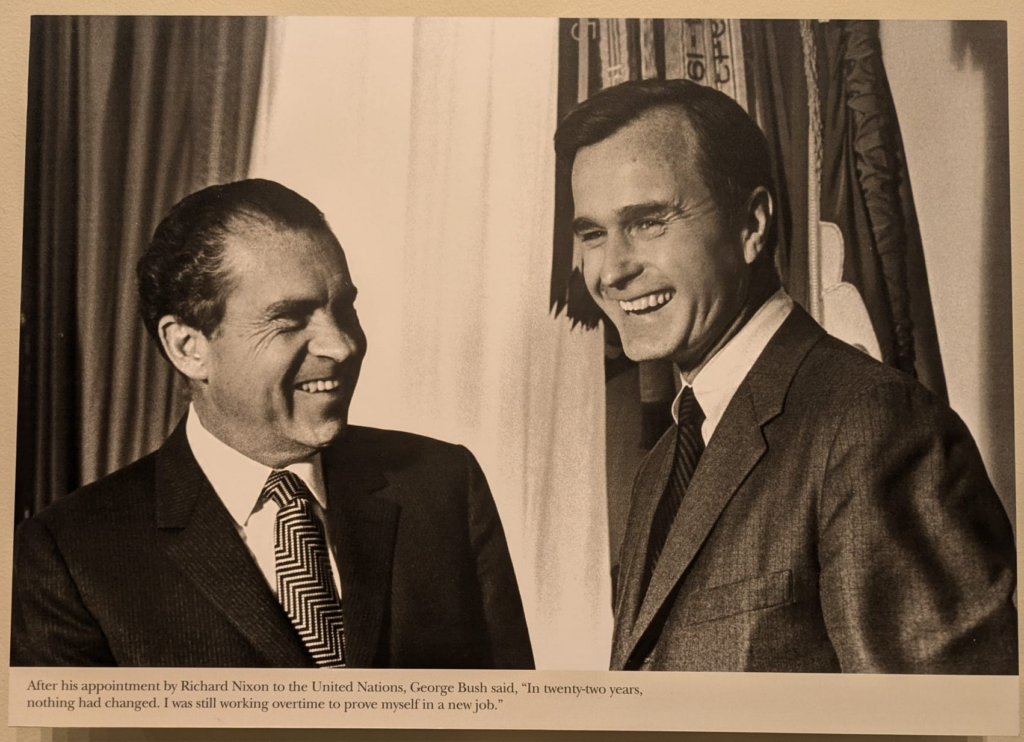

Shortly after his defeat, President Nixon tapped him for the U.N. Ambassadorship. Though he was rarely involved with key foreign policy decision-making in the president’s secretive inner circle, he supported the administration’s normalization efforts with Communist China. He called for the U.N. to seat China’s Beijing government without ousting Taiwan. His proposal was ultimately defeated, but his foreign policy acumen became clear.

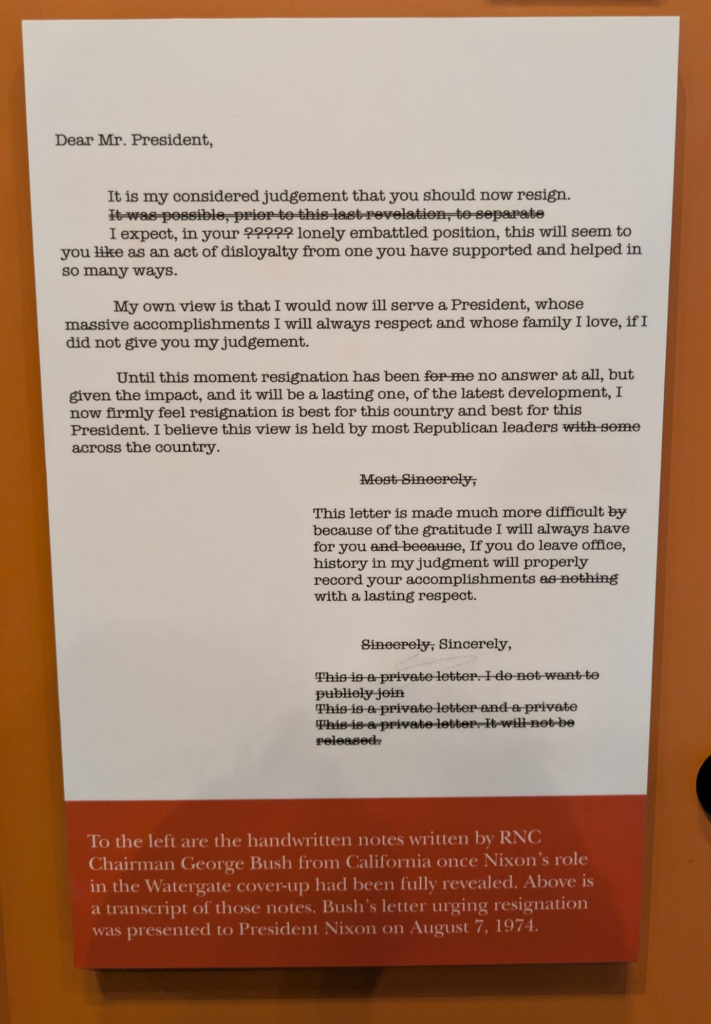

Nixon then appointed Bush as the chairman of the Republican National Committee. Facing growing public criticism from Watergate, Nixon hoped that Bush’s reputation for honesty and integrity would help contain the fallout. Ultimately, Bush encouraged Nixon to resign after he believed that Nixon had lost the support of Republicans.

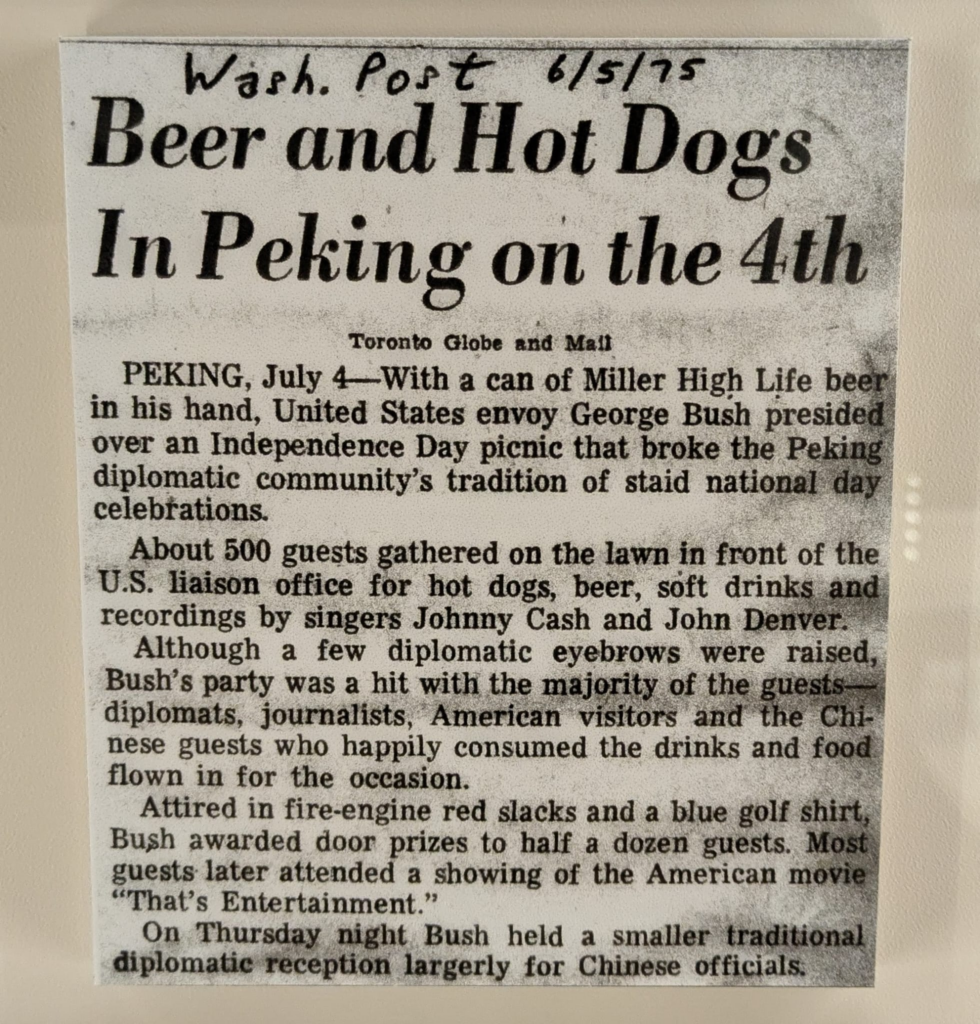

After Gerald Ford became president, Bush became the chief of the U.S. Liaison Office in mainland China. He and Barbara engaged actively with the local Chinese population, even hosting a Fourth of July celebration in Beijing.

President Ford controversially nominated George Bush as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), with authority over America’s spy agencies. His nomination drew condemnation from prominent Senators, who believed he was too political for the role, since he was widely perceived as a probable running mate for President Ford in 1976 (Ford ultimately foreswore Bush as his running mate upon his confirmation as DCI). Bush was confirmed as DCI and led the nation’s intelligence community during a period of low morale and battered public perception. Reports of CIA impropriety and leadership turnover made a compelling case for reform. Bush was well-positioned to lead reform, improving relations between the spooks and skeptical Congressmen.

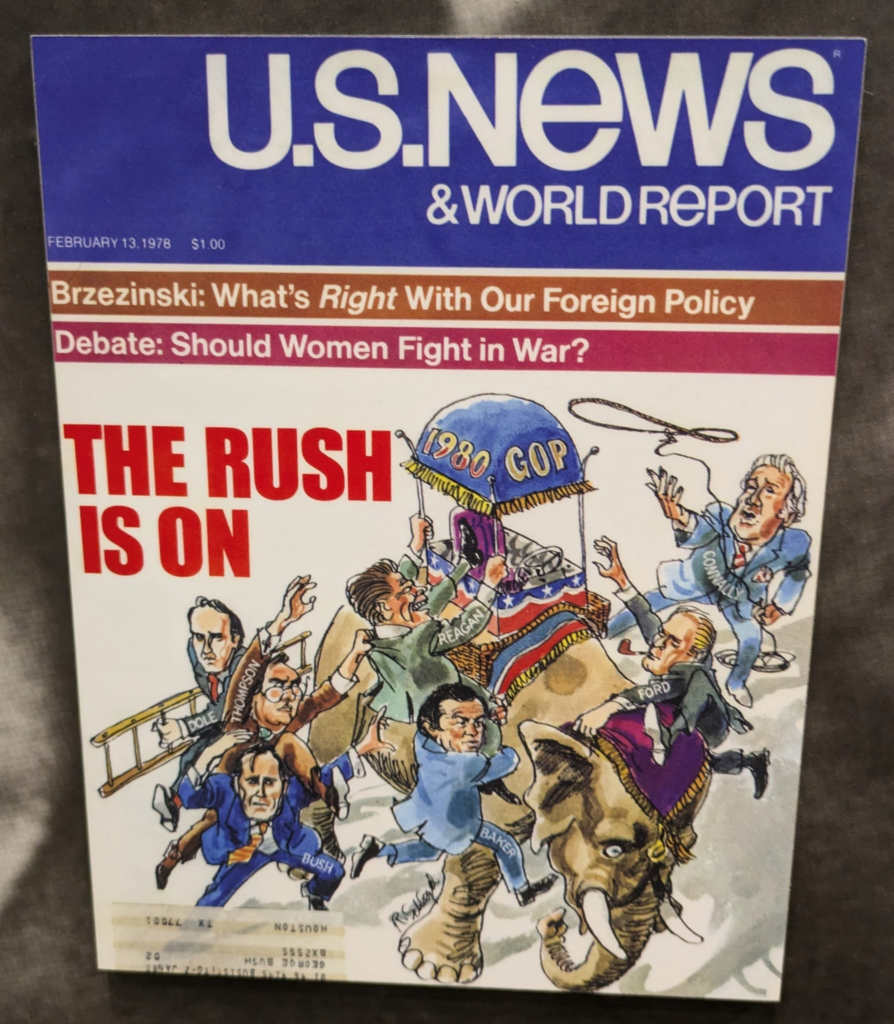

1980 Republican Primaries

The Republican Party was weak and divided when time came to choose its leadership in 1980. Conservative Ronald Reagan challenged incumbent Gerald Ford in 1976, hoping to capitalize on Ford’s association with the Washington insiders responsible for Watergate and the Vietnam War. Though Ford won the 1976 Republican nomination, Reagan established himself as a frontrunner in the party through major primary victories, a perception that was solidified after Ford’s loss to Jimmy Carter in the general election.

As Republicans began tilting further right, Bush found a difficult opponent in Reagan in 1980. Bush was far more experienced than Reagan and questioned the feasibility of Reagan’s proposals, which he thought amounted to “voodoo economics.” Bush humbled Reagan with his victory in the Iowa caucuses, prompting Reagan to respond with an impressive performance in New Hampshire. Reagan’s appeal to voters put him insurmountably ahead, winning twenty-nine of thirty-three primaries. He chose George Bush as his running mate to placate moderates who were put off by his conservatism.

The Vice Presidency

Bush’s experience proved useful to Reagan, even before the Republican ticket claimed the White House. After candidate Reagan spoke of his support for Taiwan, the campaign sent Bush to Beijing to assuage the concerns of Communist leaders.

Shortly after inauguration in January 1981, Bush quickly grasped the importance of the vice-president’s role “a heartbeat away” from the commander-in-chief. On March 30th, an assassin attempted to take President Reagan’s life. Bush gracefully ensured the continuity of the U.S. government and showed great deference to the recovering president. This incident deepened the friendship between Reagan and Bush.

Bush and Reagan became a close team, sharing Thursday lunches, elevating the traditionally ceremonial responsibilities of the Vice President.

1988 Campaign

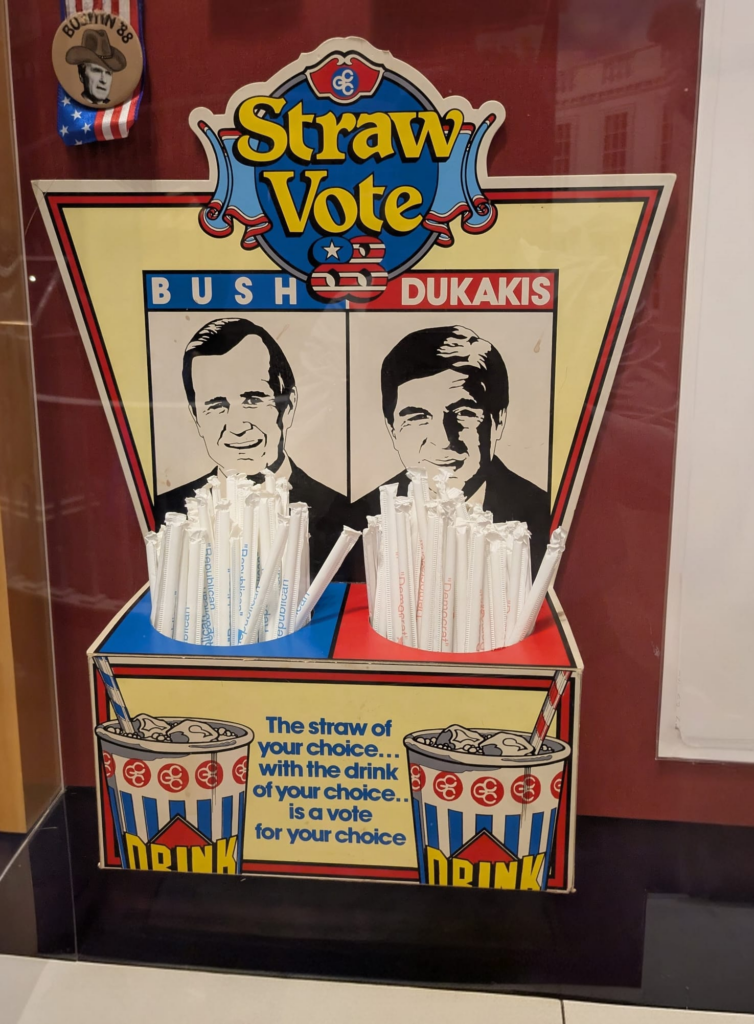

Despite his distinguished public service record, Bush started floundering in the 1988 Republican primary. He lost the Iowa caucus to Senator Bob Dole and evangelical leader Pat Robertson. He recovered in New Hampshire and the Super Tuesday primaries, ultimately taking up the Republican mantle in the August 1988 national convention in New Orleans.

Now at the top-of-the-ticket, Bush could choose his vice president. Indiana Senator Dan Quayle appealed to Bush for his youth and strong conservative credentials. The duo promised to create a “kinder and gentler nation” and preserve the low-tax economic philosophy of the Reagan years.

Bush and Quayle campaigned against the Democratic ticket of Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis and Lloyd Bentsen. Dukakis’ liberal inclination made him vulnerable to attacks concerning his stance on crime. Additionally, Bush portrayed Dukakis as out-of-touch with ordinary Americans’ concerns, accusing him of pursuing a foreign policy that was “born in Harvard Yard’s boutique” and vetoing defense-related bills.

Presidency

Foreign Policy

Panama

The two-week long invasion of Panama and deposition of its leader Manuel Noriega may be nothing more than a blip in the history of modern conflict. But as President Bush’s Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney explains, America’s brief confrontation with a despotic Central American leader unified the Bush team and prepared them to handle greater foreign policy challenges in Europe and the Middle East.

The Bush administration was initially reluctant to intervene in Latin America. Indeed, the Iran-Contra Affair, involving illegal U.S. support for anti-communist Nicaraguan insurgents, was the greatest scandal of the Reagan administration. In 1988, Noriega was indicted on drug charges by a federal grand jury, beginning the rapid deterioration of U.S.-Panama relations under Noriega. After a coup attempt failed to depose Noriega, President Reagan imposed sanctions on Panama in April 1988 and attempted to persuade Noriega to step down by offering to drop the federal drug charges against him.

In May 1989, Panama held elections that were widely criticized for being unfair. After the anti-Noriega coalition declared victory, Noriega declared the results of the election null. Pressure mounted on Bush to take decisive action. Instead of succumbing, however, Bush consulted with Latin American leaders before acting, winning him plaudits in the region and on Capitol Hill. The Organization of American States (OAS), hoping to deter unilateral American action, sent delegations to negotiate with the dictator. President Bush dispatched 1,881 troops to Panama to protect American citizens.

The pressure on the Bush administration further intensified after an October 1989 coup attempt led by Panamanian Major Moises Giroldi failed. Congressional opponents chastised the administration for failing to intervene in support of the coup, but Defense Secretary Cheney was adamant that Giroldi’s coup didn’t merit American support: It was an internal power struggle that wasn’t the moral equivalent of a pro-democracy movement.

Any notion of the administration’s timidity was shattered in the early hours of December 20th, when President Bush announced on a televised address his intention to depose Noriega, elevate Guillermo Endara, the winner of the May elections, and end the harassment of U.S. citizens in Panama. His decision followed OAS inaction and the intensifying vitriol of Noriega’s rhetoric that created a dangerous environment for Americans in Panama. 26,000 U.S. troops quelled significant opposition from the Panamanian Defense Forces in a day, and by December 21st, the White House announced plans to relax sanctions on Panama that had been in place since Spring 1988. The bulk of U.S. military operations ceased after five days, and Noriega surrendered on January 3rd, 1990.

Operation Just Cause restored America’s confidence in its military capabilities after its strategic failure in Vietnam a decade and a half before. The successful coordination of operations across military branches, an outcome of the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act, prepared America to face a much stronger foe, Iraq.

Iraq

Iraq had contentiously claimed sovereignty over Kuwait since Kuwait gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1961. The impetus to forcibly claim Kuwait, however, gained new momentum as the Iraqi economy faced crippling debts from its decade-long war with Iran. Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein accused Kuwait, a small but wealthy country, of exceeding Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quotas to lower oil prices and stall Iraq’s economic recovery.

Relations between Iraq and the U.S. worsened during the summer of 1990. The Bush administration initially hoped to improve relations with Hussein and dissuade him from military adventurism. Those efforts became vain when Iraq dispatched 100,000 troops to Kuwait on August 2nd, 1990, occupying the country within hours.

The Bush administration sought to rally the international community against Iraqi aggression. A series of U.N. Security Council resolutions condemned the invasion and established sanctions against Iraq. Notably, Resolution 678, adopted on November 29th, 1990, gave Iraq an ultimatum to cease its occupation by January 15th, 1991, or the international community would be authorized to use force to restore Kuwaiti sovereignty. President Bush exercised his unilateral authority by freezing Iraqi and Kuwaiti assets in the U.S. and directing the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Independence to the region. His experience as a diplomat helped him recruit thirty-eight countries in the fight to curb Iraqi expansionism.

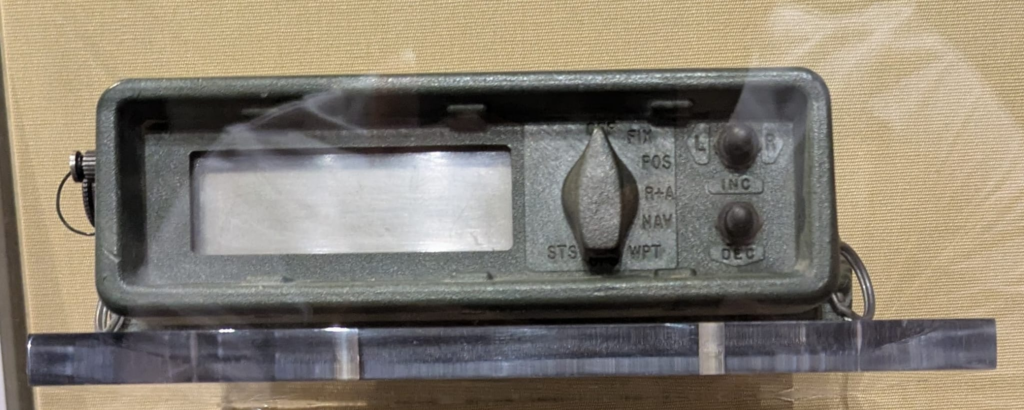

January 15th passed, and the military operation termed Operation Desert Storm began. Airpower took the lead in a first for modern warfare, quickly disabling Iraqi military facilities and infrastructure, including power stations and oil refineries. The coalition powers mobilized ground forces after Iraq retaliated with Scud missile strikes against Israel and Saudi Arabia. American technology demonstrated its might: GPS receivers, Abrams M1 tanks, and Patriot missiles gave Iraqi forces an insurmountable challenge. Just four days after the ground campaign began, Iraq agreed to a ceasefire on February 28th. U.N. Security Council Resolution 687 laid out the conditions for a permanent end to the hostilities.

Had the U.S. failed to intervene decisively, the First Gulf War might have mushroomed into a regional catastrophe. Iraq’s U.N. ambassador Abdul Amir al-Anbari claimed that Iraq reserved the right to use weapons of mass destruction. Iraqi forces poured millions of barrels of oil into the Persian Gulf, harassed Kuwaiti civilians, and practiced scorched-earth tactics against Kuwaiti oil fields.

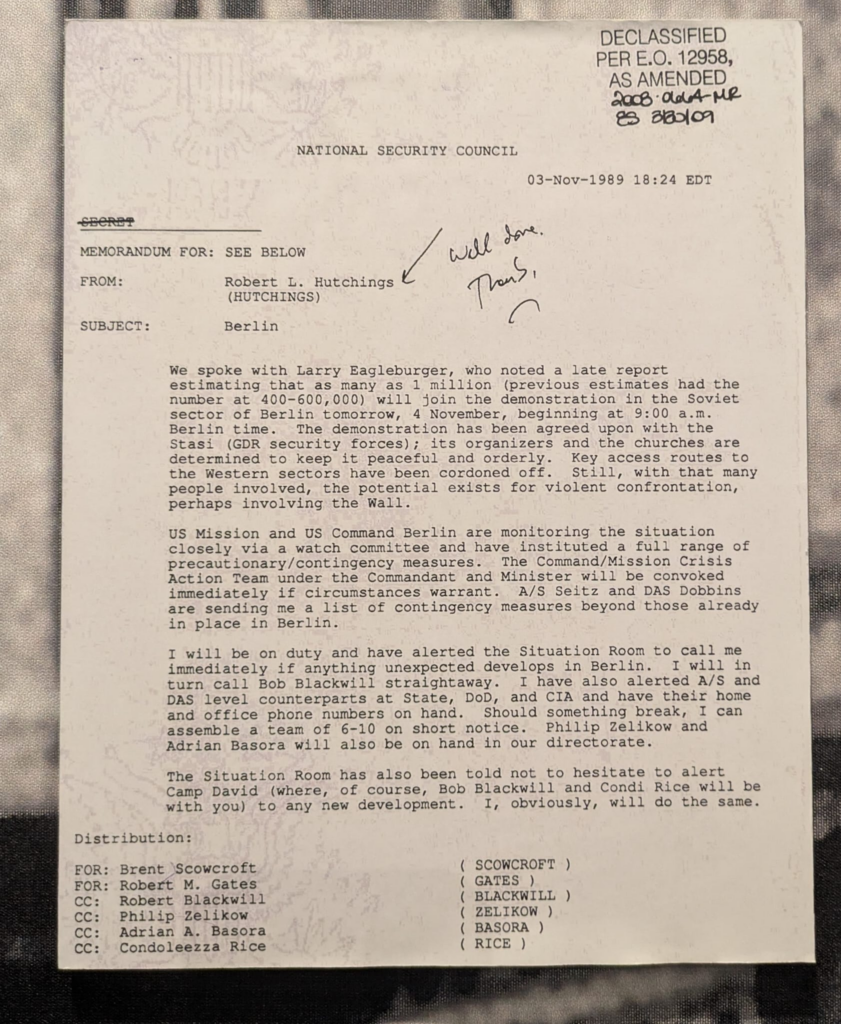

Soviet Union

When President Bush began his term, the Soviet Union was an ailing multiethnic empire. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who took the reins in 1985, forged a close relationship with President Reagan. The leaders of both superpowers enjoyed a close personal relationship, which facilitated arms control negotiations. In December 1987, Reagan and Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which mandated the destruction of ground-launched missiles with a range between 500 and 5,000 km. Reagan also called on Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall, which divided the German capital for three decades. Gorbachev’s pursuit of liberalization–through glasnost and perestroika–provided an opportunity for a diplomatic end to the Cold War.

Strobe Talbott’s description of President Bush’s role as an “air traffic controller” who “brought the Soviet Union in for a relatively soft landing on the ash heap of history” accurately describes the complexity of the president’s task. Gorbachev’s reforms catalyzed the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as nationalist movements toppled iron-fisted communist regimes. As America’s most trusted partner in the evolving political landscape of Eastern Europe, Gorbachev found himself in a precarious position: The mounting tension between democrats, like Boris Yeltsin, and communist hardliners threatened cataclysmic violence in a nuclear-armed region.

In 1991, the Bush administration pursued a hybrid policy of supporting up-and-coming democratic leaders while backing Gorbachev’s reforms. President Bush signed the START arms control treaty with Gorbachev in July 1991, before an attempted coup in August shredded the last vestiges of communist authority and brought the democrats to the political fore. On December 25th, 1991, the Soviet Union gave way to twelve new republics.

In Fall 1991, Secretary of State James Baker expressed that the U.S. would recognize and support post-Soviet republics, as long as they committed to liberal democratic values. Congress passed the bipartisan Freedom Support Act (FSA) in July 1992, based on priorities that President Bush enumerated in an April 1st speech. The FSA allocated funding for economic stabilization, humanitarian assistance, and non-proliferation, and provided technical assistance to civil society organizations.

President Bush demonstrated magnanimous statesmanship in guiding Eastern Europe and Central Asia to a brighter future. As David Halberstam writes in War in a Time of Peace, Bush “did not try to grab too much credit for the collapse of communism, for what had transpired was a triumphal victory for an idea rather than for any one man or political faction.” Bush’s unwillingness to sell his Cold War victory aggressively to the American public may have cost him another term in office. Had he instead chosen to jettison cautious restraint, he might have emboldened Soviet hardliners and derailed the project of freedom. President Bush’s conviction that “process always [takes] precedence over image” elevates him to the pantheon of American patriots.

Domestic Policy

Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), signed by President Bush on July 26th, 1990, may be the most cherished legislative victory of the Bush years. However, the story of the ADA begins far before the Bush administration.

Federal protections for disabled Americans originated in the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The Act forbade the federal government, federal contractors, and other recipients of federal funds (like universities) from discriminating based on disability. However, the Rehabilitation Act did not immediately protect the rights of disabled Americans: The federal government did not author regulations for Section 504, the key provision of the law, leaving it up for vague interpretation. In April 1977, a group of disabled Americans staged a monthlong protest to highlight the inadequacy of the federal government’s enforcement of the law. They argued that Joseph A. Califano, the head of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, the federal agency tasked with implementing Section 504, was looking to weaken requirements for disability accommodations. (Califano and the Carter administration ultimately relented, and 504 regulations were authored exactly according to the law.) Disability activists scored other legislative victories, including the 1975 signing of the Education of All Handicapped Children Act, which enshrined disabled students’ right to a public education.

The ADA sought to broadly extend the protections of the Rehabilitation Act across public life, just like the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The ADA’s legislative history began with the National Council on Disability’s 1986 report Toward Independence, which emphasized the absence of legal protections for disabled Americans. Congress appointed a Task Force in 1988, and Senator Lowell Weicker and Representative Tony Coelho co-sponsored the first version of the ADA that year. A revised version of the bill passed the Senate in 1989 and the House in 1990 before arriving at the president’s desk. Notably, the ADA included protections for Americans with HIV, drawing controversy.

Drawing from the lessons of 1977, the ADA established strict implementation timeframes. Employers with 25 or more employees, including state and local government bodies, were required to adhere to anti-discrimination requirements by July 26th, 1992. Constructions and alterations to commercial facilities initiated after January 26th, 1992, had to be compliant with accessibility standards.

Clean Air Act Amendments

President Bush, along with his Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) head William Reilly, spearheaded the passage of 190 additions to the Clean Air Act of 1970. The Amendments tightened automotive pollution requirements, revised the list of controlled pollutants, and introduced a phase-out of ozone-depleting chemicals. The Amendments created a cap-and-trade system for pollutants and established a training and unemployment benefits scheme for workers displaced by the new requirements.

The Clean Air Act Amendments were ahead of their time and offer inspiration for upcoming climate legislation. The cap-and-trade system curtailed the release of ozone-depleting substances, fulfilling America’s responsibilities under the Montreal Protocol. Americans’ health improved dramatically, too. Between 1990 and 2015, particle pollution levels improved by 36%, and the 41 areas that suffered from unhealthy carbon monoxide concentrations in 1991 now meet national standards. Market-based limits on sulfur dioxide emissions improved the health of marine ecosystems.

Legacy of Service

President Bush would not receive another term in office. His opponent in 1992, charismatic Arkansas governor Bill Clinton, understood that Americans’ priorities had turned inward after the defeat of the Soviet Union. The Bush administration’s inability to acknowledge and act decisively at the onset of the 1990-1991 recession damaged its public perception. President Bush alienated his conservative base when he broke his campaign pledge in June 1990 of imposing no new taxes. Though his political abilities may have been limited, President Bush epitomized service. The National and Community Service Act of 1990 codified his lifelong ethic of giving back, creating a private, nonprofit foundation to encourage Americans to participate in community service.

President Bush never deviated from his conviction that America was stronger when it partnered with other countries, including historical adversaries, to reject aggression. His measured approach to foreign policy, which was driven by the facts of the situation, offers valuable lessons for policymakers navigating today’s multipolar world.